Within the field of Oriental medicine, Shiatsu is nowadays considered to be an established modality, especially when viewed from a Western perspective. Within the field of Shiatsu itself, there are often said to be distinct styles and one of the most easily identifiable is held to be Zen Shiatsu, created roughly half a century ago in Japan by scholar, thinker and innovator Masunaga Shizuto.

This series of articles will pursue three main threads. One of them will be to provide a historical account of the birth of a distinctive and highly influential style of Shiatsu and describe the process within the larger context of Japanese history and culture. In doing this, we will also examine Massunaga’s creation in terms of both tradition and innovation. Further, we will attempt to identify the attributes of Zen which gave it its name, and which might distinguish this style from other Shiatsu forms. A major theme which will emerge as part of these investigations will be the relationship between Masunaga’s creation and the broader tapestry of Oriental medicine, from which he drew both inspiration and direct influence on many levels.

No assumptions are made as to the amount of specialised knowledge an individual reader may have. Instead, it is accepted as a given that various readers will be interested and knowledgeable in different areas and to varying degrees. For some there will be superfluous detail in places, while for others certain basic concepts will already be understood and can be skimmed through fairly rapidly.

Bu Chris McAlister

The Birth of Zen Shiatsu

Zen Shiatsu is a recently founded therapeutic style. However, due to its use of concepts and practices from the traditions of Oriental medicine, we may usefully regard it as a young and vibrant branch on an ancient and powerful tree.

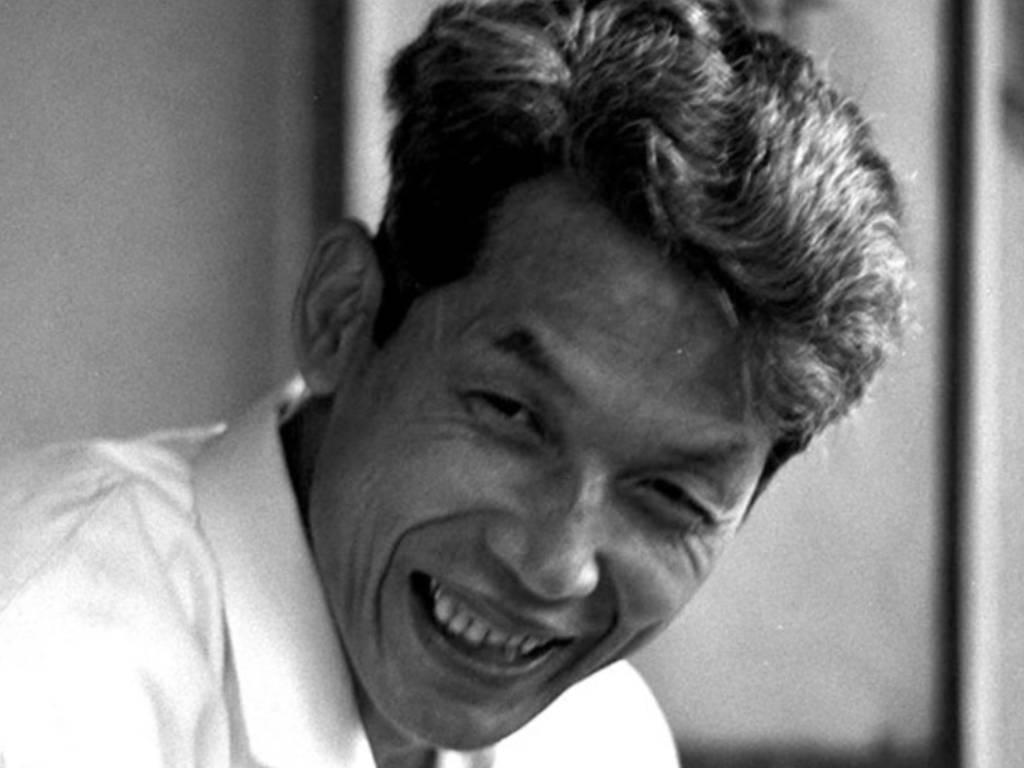

The gradual formation of the style that came to be known as Zen Shiatsu is primarily the work of one man: Shizuto Masunaga. Born in Kure, Hiroshima prefecture, Japan, in 1925, his first professional field was psychology, in which he graduated from Kyoto Imperial University in 1949 [1]. Moving on to bodywork, following his mother’s influence – she hosted Shiatsu classes with master Tenpeki Tamai in the Masunaga family home – he later graduated from the Japan Shiatsu School [2] in Tokyo under Tokujiro Namikoshi. From 1959 he taught clinical psychology for ten years at the school, which held at the time, and holds still to this day, the exclusive right to licence Shiatsu practitioners in Japan [3].

We can only guess at the exact stages in the process of development and separation that took place in Masunaga the teacher and practitioner, but by 1968 he had established his own school: the Iokai Shiatsu Centre. From here, and together with a dedicated group of students, he proceeded to lead the process of deconstruction and reconstruction which would gradually lead to the development of Zen Shiatsu .

In terms of deconstruction, Masunaga went to extreme lengths to dismantle the style he had inherited – the Namikoshi Shiatsu of his teacher [4]. As far as reconstruction goes, he was able, as we shall see, to put together a holistic method which integrated the vital, energetic theories of traditional Oriental medicine [5] with key aspects of the result-based science of the West. The story of Masunaga’s efforts entails not only his bringing the spiritual essence back into Shiatsu [6], but also significant contributions to the evolution of Shiatsu through developing theories and practices unique to his system.

Shizuto Masunaga created a style of Shiatsu that re-integrated its original core of spirituality and vital energy. Following his special interest in exploring the mental, emotional, and spiritual components of the human entity, he crafted a system that merged ideas from Western psychology and physiology, traditional Chinese medicine and Zen Buddhism.

Because Masunaga was able to frame traditional Eastern concepts in conventional, modern Western terms, his style, Zen Shiatsu attained a wide appeal and has become perhaps the most popular form of Shiatsu internationally.

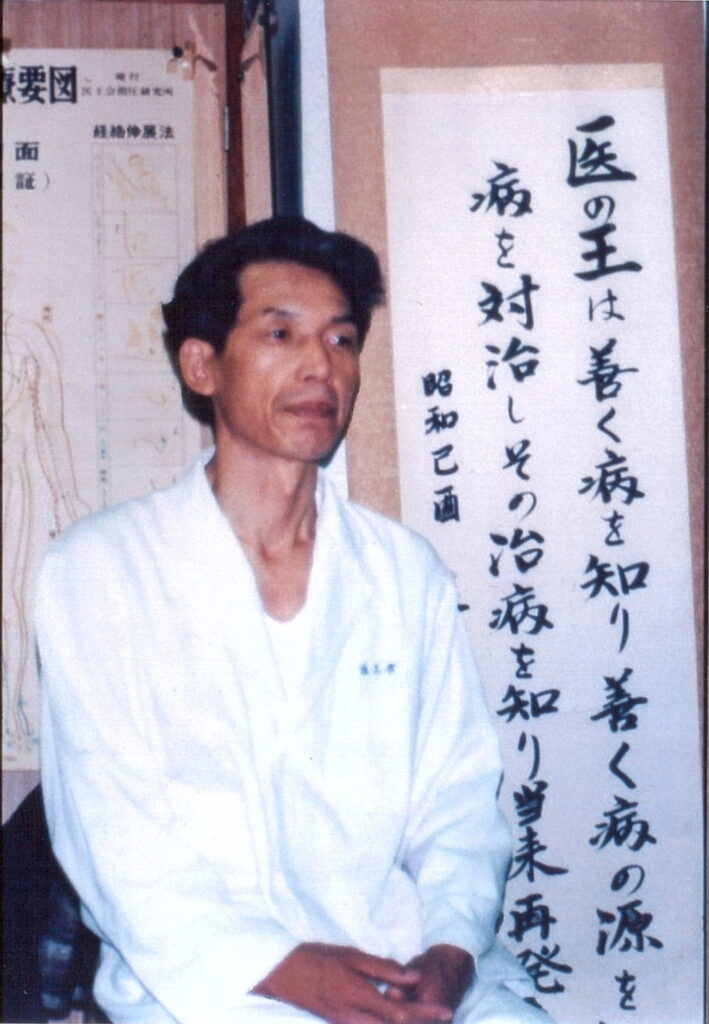

“Ee-no-o” – meaning King/Emperor of Medicine.

The Iokai (医王会 ; Ee-Oh-Kai) Centre [7] still exists, even though its founder passed away in 1981. The name Iokai says a great deal about the ambitions of its leading figure. Translated literally, it would mean: Emperor of Medicine Association. This may strike the Western reader as somewhat lacking in humility, and thus the following set of contextual references may prove helpful.

“Zen” in Shiatsu

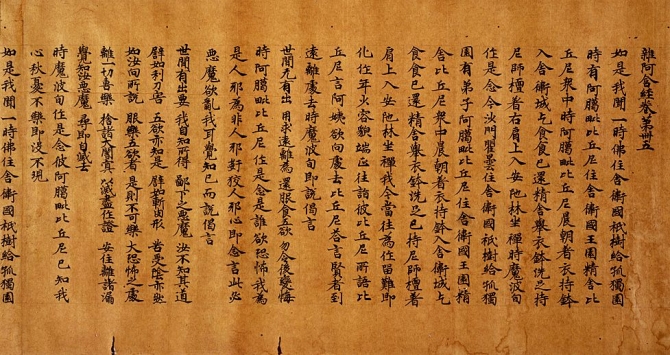

Masunaga’s attention had been seized by a certain passage in the Buddhist sutra known in Japanese as Zoagon-kyo. The passage in question explains the importance of a thorough and spiritual (what we might today call “holistic”) approach to healing. The Emperor of medicine should, it urged, thoroughly examine the nature of disease, clearly identify origin and cause, treat the disease but also care for and enlighten himself as to the constitution of his own being.

In this short passage we find a concise description of some of the key tenets of traditional Oriental medicine: the enquiry into the nature of disease; its origins and causes as well as its effective treatment, but also, and perhaps above all else, the caring for of one’s own person and the path to enlightenment through the calling of healing.

These ideas are not often stated quite this directly by either modern or traditional practitioners and teachers of Oriental medicine, but Masunaga seems to have been very clear on this point: the way of healing is a way to enlightenment. This of course goes a long way to explain why generations of people throughout the ages and in all cultures and situations in life have felt compelled to dedicate their lives to healing.

Thus, healing work should in no way be mistaken for a selfless giving of time, energy and life resources. It is a way in itself with its own promise of reward. In the preface to his seminal English text from 1977, “Zen Shiatsu”, we find the following lines written by Masunaga:

“In Zen it is important to have a good master to learn from. In Shiatsu your patient is your master. You can achieve satori by treating disease and restoring health.”

This underscores the importance of the word Zen in the context of the name given to Masunaga’s style of Shiatsu.

Further on in this chapter we will be taking a closer look at the practical aspects of the style, and in particular the emphasis on “natural pressure”, fluid movement and ergonomic posture. Once we have done this, we will be able to consider the question of whether or not the word “Dao” might have been equally as fitting, if not more so, to describe the essence of Masunaga’s contribution to Shiatsu.

There are two interesting stories regarding how Masunaga eventually came to name his style Zen Shiatsu. The first is the one with which the majority of practitioners tend to identify. The story goes that either Masunaga treated a Zen monk or that a monk witnessed Masunaga giving a treatment to a third party. Either way, it is related that the monk then likened what he had experienced, or seen, as Zen practised between two people.

The other story is somewhat less appealing to practitioners of Zen Shiatsu, but perhaps no less important in the larger context of Oriental bodywork therapies making inroads into Western cultures. This story relates that during the process of translating Masunaga’s book “Shiatsu” into English, his collaborator, Wataru Ohashi [8], suggested the name “Zen Shiatsu”. Ohashi argued that such a name would have a far greater appeal among Western readers. This has proved to be a powerful insight, and the story is not likely to be dismissed out of hand by those aware of Ohashi’s penetrating knowledge of the human psyche, and, on a practical level, of what sells.

What is certain, however, is that Zen Shiatsu has become a recognised and popular style of Shiatsu in the Western world, notwithstanding its relative obscurity in Japan. This obscurity is partly explained by the complete monopoly still enjoyed by the Namikoshi family organisation over the issuing of state licences for Shiatsu practitioners in Japan. The other major factor is the current low status accorded most forms of traditional Japanese and Oriental art, with a few notable exceptions (sumo, kabuki and ikebana being the most prominent among them).

The Two Sides of Masunaga

1. The scholar sage

This brings us to the two very different sides of Masunaga’s life story. On the one hand, it is possible to see Masunaga as a modern example of the scholar sage, a universal figure known and revered throughout Oriental history. On the other hand, he is very much able to be regarded as a product of his own particular time and place.

Ultimately, we will find that he can perhaps best be viewed as an exceptionally gifted individual who managed to successfully combine these two polarities. From the particulars of time and place, but equally from the resources of tradition, Masunaga created a thing of lasting value that outlived his own physical existence and continues to thrive.

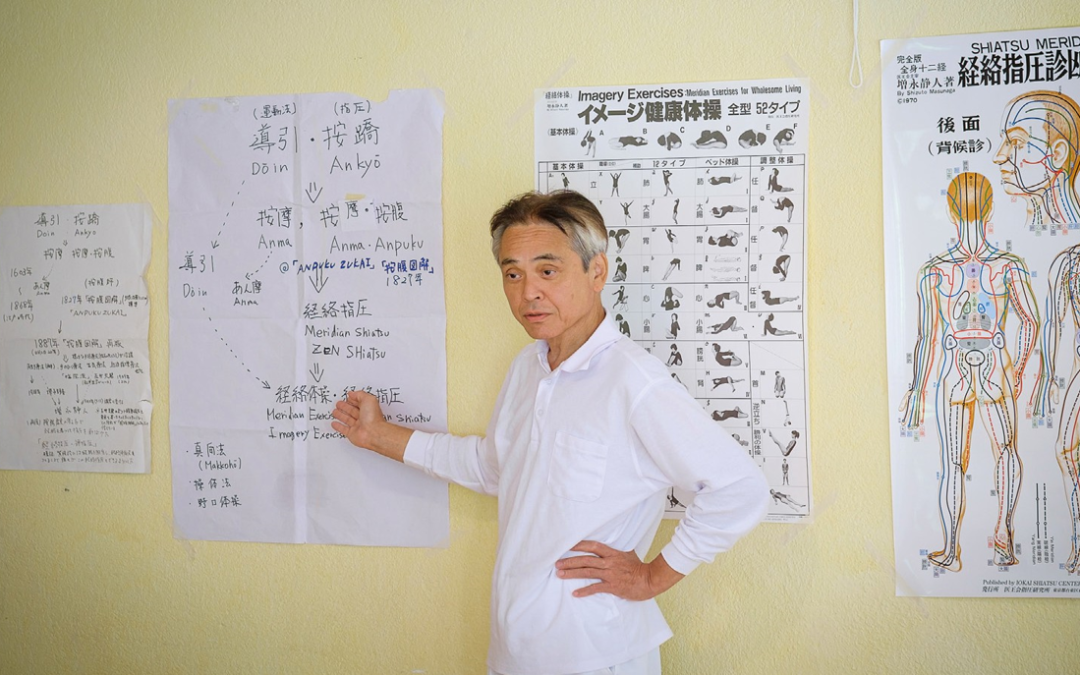

If we choose to regard Masunaga as one in a long line of scholar sages, we have much to support our view. As mentioned above, he initially studied psychology to a professional level. Augmenting this, he moved on to incorporate not only the art of bodywork, but also the field of movement. As if to emphasise the importance of the latter, his other translated text published in 1987 was called: “Zen Imagery Exercises” [9].

In this later book (fluidly translated by Stephen Brown), we see the second major result of his life-long investigation into what he called “the echo of life”. The main body of the text consists of several series of exercises. The pronounced aim was to introduce the reader to simple movements, which would awaken and kindle the relationship of the individual to his/her own life energy or Ki (Qi).

In this text he also developed his descriptions of the meridians of Oriental medicine, and it is here that we encounter yet another area of endeavour in this remarkable man’s life.

Masunaga was a man who seems to have ceaselessly analysed, interpreted and applied traditional as well as modern streams of knowledge. His work was one of re-evaluation, re-interpretation, and synthesis. This synthesis was achieved over a lifetime and through the dual processes of mental exertion and practical application. We can infer in his work a spiral-like process of continual reassessment. By this we can understand a relentless instinct to discover and learn, but also to thoroughly test all theories and discoveries in the clinic – that most exacting of arenas.

These various attributes and accomplishments, when taken together, bear the hallmark of the scholar sage: endeavour in several parallel and connected fields; traditional knowledge painstakingly accrued; modern theories and practices examined and tested and, finally, a personal synthesis of the most effective and rewarding components contained within a substantially new creation.

2. A Man of his time

If we now take a look at the reverse side of the dichotomy, we find a man completely in harmony with his zeitgeist: the spirit of the age in post-war Japan. Ever since the Meiji restoration in the 1800’s, Japan had been undergoing a rapid transformation. In a relatively short period of time Japan transformed itself from a hermetically sealed, feudal culture to a modern, progressive society, open and willing – almost desperate – to assimilate that which had previously been strictly forbidden: Western values and practices, and of particular interest to us, the natural scientific method.

In medical terms, this meant anatomy and physiology and the modern practices of Western medicine. The crisis for the traditional Oriental healing arts that this inevitably precipitated took many forms, ranging from complete abandonment through partial integration to outright denial and entrenchment. The crisis had, however, merely begun and was to both accelerate and intensify.

By the end of the Second World War, Japan was utterly devastated. In material terms, food was scarce, infrastructure destroyed and national health depleted. The most naked symbols of this were, of course, the southern cities of Nagasaki and – even more notably – Hiroshima, Masunaga’s birthplace, both of which were annihilated by atomic bombs.

Spiritually, the Japanese were no less diminished at this time. The Emperor, having traditionally enjoyed the status of a god, had been thoroughly humiliated by the “cultureless” Americans, and shown to be no more than an ordinary mortal.

It is probably impossible for a modern, Western reader to imagine how this might have felt or gauge the impact it must have exerted on an entire people. What history has objectively and emphatically shown us, however, is that the consequences were far-reaching in the combined fields of the arts – expressive and stage arts no less than medical and martial arts.

The in-depth examination, which had steadily progressed during the past century, now intensified exponentially. A distinct feeling of life-or-death importance seems to invest this period, together with a fierce need to reinvent and re-invigorate the culture and identity of Japan.

We can see the consequences in such diverse fields as Butoh dance, Ryodoraku acupuncture, Aikido, Karate, macrobiotics, and, not least, Zen Shiatsu, although in each case the ratio of assimilation to conservation varies appreciably.

Whereas Butoh dance is a superb example of dance pioneers searching backwards towards the roots of “Japaneseness” in their art, Ryodoraku acupuncture is, by contrast, a system that was developed by Nakatani, its founder to reinterpret, explain and practise acupuncture through the application of certain key conceptual tools derived from modern, Western medicine.

Aikido came into being as an urge to derive the maximum effectiveness out of the traditional fighting arts of jujitsu and swordsmanship, while framing them overtly in the language and practice of love and harmony. Aikido became a modern, synthetic art steeped in the time-honoured traditions of Japanese martial arts [10].

George Ohsawa [11] founded Macrobiotics in an attempt to redefine the principles of Oriental philosophy (primarily yin and yang) and apply them to the daily bread all humans ingest, in the wider service of world peace and harmony.

There are numerous examples of this process of re-invention, re-interpretation, and re-incorporation right across the board in Japanese cultural life – including Shintaido, Sotai [12], Noguchi Taiso as developed by Michizo Noguchi and the Seitai and Katsugenundo exercises developed by Noguchi Haruchika [13]. Synthesis of varying degrees is the common denominator. Zen Shiatsu is another prime example of this phenomenon. It is, after all, highly likely that some or all of these movers and movements were well known to Masunaga. One famous example is the Makko Ho exercises developed by Wataru Nagai [14] (1869-1963). At age 42, Nagai suffered a stroke leaving half his body paralysed. His doctors told him he would likely have to spend the rest of his life half paralysed, dependent on support and probably unable to work. Nagai developed the Makko Ho exercises while looking at a textbook on Buddhism at the home of his father, a Buddhist monk.

(To be continued)

Editor’s notes:

- [1] Kyoto Imperial University is now called simply Kyoto University

- [2] Now known as Japan Shiatsu College

- [3] In fact, two other schools have the right to issue state licenses: Kuretake and Chosui Gakuen. The author is making the point that they all come from the same crucible of the Namikoshi school, which is technically correct.

- [4] It could be argued that Shizuto Masunaga had to dismantle his inheritance from two teachers: Tenpeki Tamai and Tokujiro Namikoshi.

- [5] He was influenced by various well known authors and by the presence of Izawa sensei, who taught oriental medicine at the Japan Shiatsu College.

- [6] To this extent, he has preserved the legacy as witnessed in the final chapter of Tenpeki Tamai’s “Shiatsu-ho”, which advises readers to recite the Lotus Sutra at least once a day to open their heart.

- [7] The Iokai Shiatsu center of Tokyo is currently run by his son Haruhiko Masunaga.

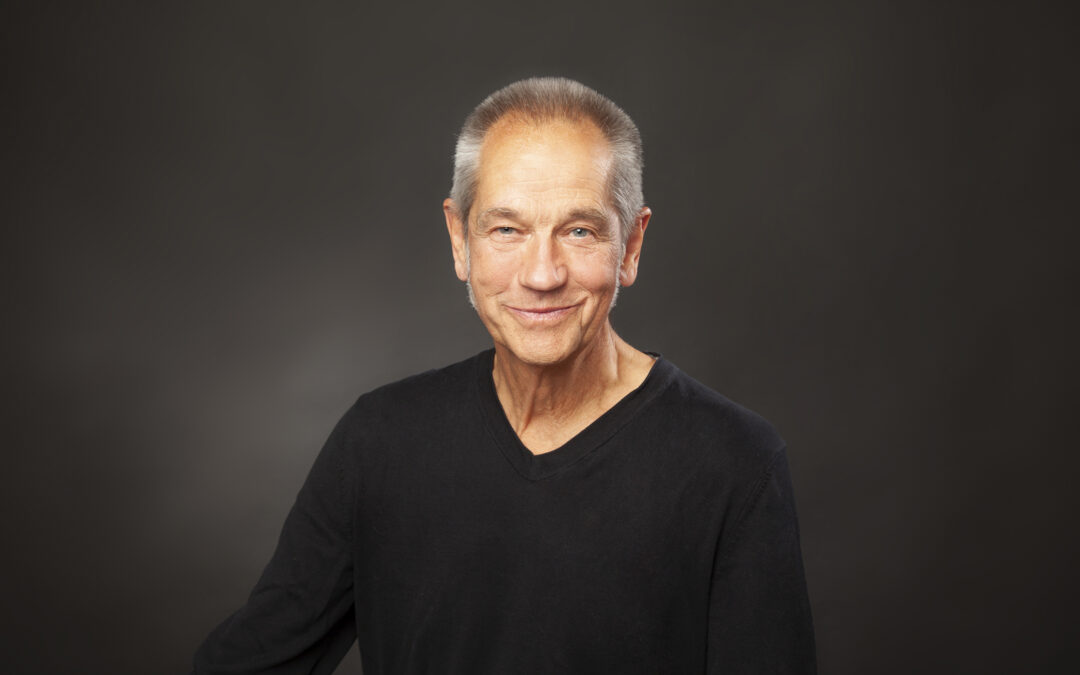

- [8] Read the interview of Ohashi, where he describes how he changed the title of Masunaga’s book.

- [9] Zen Imagery Exercises: Meridian Exercises for Wholesome Living; Shizuto Masunaga, Tokyo, NY: Japan Publications, 1987

- [10] Read “Those Aikido masters who spread Shiatsu“ by Ivan Bel

- [11] George Oshawa (1893-1966), born as Nyoichi Sakurazawa, founder of Macrobiotics had a major influence on several Japanese Shiatsu masters. To find out more, read: “L’histoire des pionniers Japonais en France – Les Années 50“ by Ivan Bel

- [12] Sotai-ho (操体法) is a Japanese form of manual therapy, invented by Keizo Hashimoto (1897–1993), a Japanese doctor from Sendai. The term So-tai (操体) is the opposite of the Japanese word for exercise: Tai-so (体操). According to its inventor, it is based on traditional East Asian medicine (acupuncture, moxibustion and bone setting or sekkotsu) combined with his knowledge of modern Western medicine.

- [13] Seitai (整体) refers to a healing method with multiple origins formalised by Haruchika Noguchi (1911-1976) in mid-20th century Japan. The term means “correctly aligned body”.

- [14] To find out more about Makko-Ho and Dr. Wataru Nagai, please read “Trois pratiques d’étirement (1) – Le vrai Makkô Hô japonais“ by Stéphane Cuypers

Author

- Shizuto Masunaga: his way of diagnosing – part.3 - 31 May 2023

- Shizuto Masunaga (part 2): His Creation - 9 January 2023

- Shizuto Masunaga (part.1): a genius on shoulders of giants - 6 October 2022

- The Blackened Pot - 15 June 2022