While not much is known about the infancy of Chinese medicine, it is known that proto-religions and proto-medicines were the work of shamans all over the world. Both healers and intercessors with the spirit world, these men and women are at the origin of the first conceptions of health. The etymological study of points in the Chinese language makes it possible to find a “historical” trace of their existence.

The whole history of medicine, anywhere on the planet, begins with shaman-healers trying to heal the populations of villages who were in their care and to explain what disease is. This aspect of human history has been put forward in the four corners of the globe thanks to the so-called culturalist anthropology[i] by thinkers such as Ruth Benedict or Margaret Mead, then via structuralist anthropology[ii] whose leader was the immense Claude Levy-Strauss. The perception of invisible forces (spirit world) by shamans naturally leads to the following conception: a disease is the result of the interference of spirits in the proper functioning of the body. These spirits are then called evil (to distinguish them from good spirits) because they come to disturb health. In ancestral Chinese medicine (we are talking about the “classical” conception of this medicine and not the “traditional” version manufactured by Mao and the communist regime), the place of these evil spirits called Gui (or Demons) is foremost.

Without going into the details of this family of points, you should know that there are 13 demon points that were listed for the first time by the famous doctor Sūn Sīmiǎo 孙思邈 (581 – 682), author of the Qianjin Yaofang (千金要方) (the “Essential prescriptions worth a thousand gold coins”), a work that is still under study today in Chinese medical schools. He is also the one who first wrote the term Zhōngyī (中医), not in the sense of “Chinese medicine” as today but rather “median/middle medicine”[iii]. These points therefore reflect a distant shamanic past to Chinese medicine.

First interesting remark, Sun Simiao lived in the 7th century AD. But the demon points he talks about are very old since they are the legacy of shamanic practices. However, the theory that demons had to be expelled or calmed to cure the disease persisted throughout Asia until the 18th century. Taoists in China and Shintoists in Japan are usually in charge of performing rituals to deal with demons. This changed little by little with the influence of Western medicine. One thing, however, is certain: Sun Simiao did not live in the shamanic period that saw the birth of the Demon points. He therefore had access to this knowledge either through old works or via shamans who still existed in the 7th century.

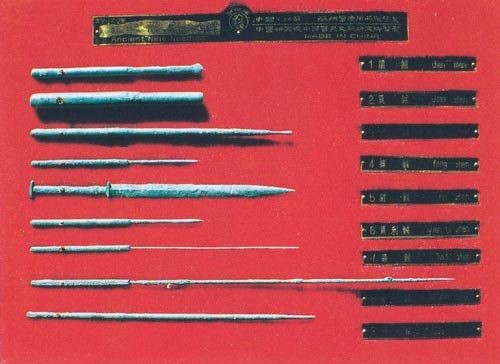

Second remark: About the book the Classic of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi Neijing – 黄帝内经) that was written between 500 and 220 BC, it relates an interview between the Yellow Emperor and his Prime Minister Qi Bo (or T’chi Pai in the EFEO system) at the time when Chinese doctors were forsaking the use of “stone punches”[iv] for metal needles (more precisely bronze needles)[v] . It is therefore estimated that the book recounts a period (real or mythological) that would date back at least 4500 years. That being said, some Chinese estimates date the existence of the Yellow Emperor to 2600 BC. Archaeological excavations increasingly demonstrate that the ancient mythological kings are in fact people who actually existed[vi], but this is different debate.

Coming back to the Yellow Emperor Classic. In what remains the reference of Oriental medicine (even if it is no longer the first written record on medicine[vii]), we understand that it is a mutation of medicine, evolving from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age[viii]. In other words, we move from the proto-medical period under the aegis of shamanism to the entry into classical medicine directed by a more scientific mind where the causes of diseases are to be found in external climatic aggressions (first the Cold, then much later the Hot) and finally in internal imbalances (emotions in particular). Therefore, when in the 7th century Sun Simiao made a list of 13 demon points, he did not invent anything: he cited older sources such as those found in Mawangdui. The 13 demon points are therefore quasi-archaeological traces of these ancient times of Chinese medicine.

Líng: the healing shaman

Faced with the presence of demons disrupting health, you basically have two choices. Either to expulse them with the help of ceremonies, incantations and healing plants (this medicine is called Zhù yóu 祝由[ix]), or to calm, disperse or harmonize them via the body. In all cases the patient had to call on a shaman-healer. The presence of the shaman in caring has left traces since it is found in the names of the current points. It is a family of 5 points with the character Líng (灵).

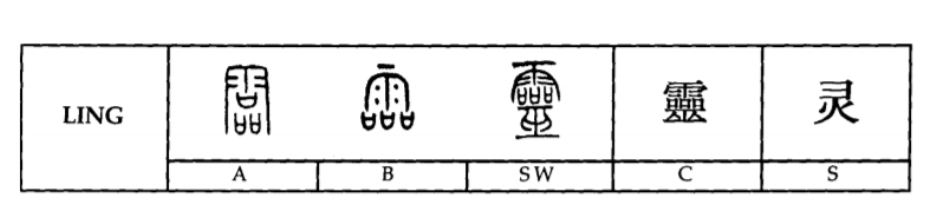

In the excellent reference book “The Spirit of Points” by Philippe Laurent[x], we find a beautiful explanation of the evolution of the Líng character.

In its oldest form, it is a case of obtaining rain with large drops that fill containers (bowls, jars?). Another more plausible interpretation would be three mouths singing to bring rain. It is known that rain represents the concretization of Heaven’s direct relationship with Earth where Heaven fertilizes Earth through water. Rain is an important aspect of agricultural societies for which a shaman was asked to make it fall to ensure good harvests. In the “Shuōwén Jiězì” (说文解字; Dictionary of Explanation of Pictograms and Ideophonograms [xi]) there are two parallel evolutions of the character. The first depicts an offering of jade for abundant rain while the second shows two people dancing within the “work” character to bring rain. We then understand that we call on the one whose job it is to dance (or make jade offerings) to bring down an abundant rain. In other words: the shaman. In classical Chinese, the evolution follows the version of men who dance. The raindrops have become square and this time they can be clearly interpreted as the repetition of the character of the mouth (口 kǒu), which then gives “those who sing and dance to make the rain fall” which is probably the oldest function of the shaman among primitive populations.

Therefore, there are five very ancient points on the body related to shamans who fight against demons and that make it possible to “bring down the rain”, that is, to attract Heaven in its beneficial aspect to rebalance the harmony. Let’s see what are the current meanings of the word líng in the You Feng Dictionary:

- Coffin, funeral casket: this is the semantic evolution of the psychopomp function of shamans that allowed the dead to reach the spirit world and the deceased spirits to communicate with the world of the living.

- Skilful / fine / intelligent: this definition is fascinating, because to say this the Chinese sometimes use the expression guǐ jī líng 鬼机灵 (classical: 鬼機靈) which is word for word “demon – occasion/luck – shaman”, or skilful as a shaman who expresses himself on the occasion of the presence of a spirit/demon. Or subtle as a shaman who seizes the chance to make a spirit/demon speak.

With these definitions it is clear that the “shaman” points are inseparable from the “spirit/demon” points and that they will make it possible to intercede with them in order to regulate their harmful actions.

The shaman is an earthly person. His offerings and actions start from Earth and go up in supplication to Heaven. His movement is therefore ascending (one could say Yin). You need to be subtle to speak to Heaven. This is why the Líng is considered as the subtle part of the Shén, totally immaterial, because it leaves the incarnation to go to Heaven. The Shén descends from Heaven to be embodied and can be seen in physical manifestations such as the shine of the eye or skin complexion for example. In this descending movement the Shén is therefore a manifestation of heavenly Yang. This is why Líng and Shén will have a crucial importance in the comings and goings of the Spirit in order to regulate the Demon points on the most sensitive part of our being: psychology and emotions.

List of Líng points

To fully understand the meaning of the Líng character it is now possible to leave it in Chinese, because it is, as we have just seen, a concept (Pure Spirit of the Shén) or to return to its first definition: the shaman. Feel free to play with these different interpretations.

- 2Heart: Qingling; “vitality of the Líng” which can now be interpreted as “the strength of the shaman or the Spirit”.

- 4H: Lingdao; the “Way of the Líng/Shaman”, also translated as “Way of Awakening”.

- 24Kidney: Lingxu; “rampart of the Líng/shaman” but before being made of stone, a rampart was mainly a mound of earth, a high place (see point 10DM for more explanations)

- 18Gall Bladder: Chengling; “carries the weight of the Líng/shaman”, usually translated as “parietal”. These are the two parietal lobes of the skull which, like hands stretched out to Heaven hold the brain, seat of the Líng, its mental activity.

- 10DuMai: Lingtai; the “mound of the Líng/shaman”, a high place (hill, mountain, mound) where the shaman stood to make his incantations. Closer to Heaven in a way…

If we look at their therapeutic actions, we find a list of quite interesting effects[xii] many of which relate to breathing and lung disorders. That should make you think.

- 2H: circulates Qi and Blood, calms shoulder or arm pain in case of swelling, softens tendons, treats headaches with cold chills.

- 4H: treats “madness” psychogenic states of agitation, unblocks the Lung in autumn, coupled with 15VG it releases emotional aphonias, relaxes muscles and tendons, calms the Shén, anxiety, nervousness, treats precardialgia, subjugates rebellious Qi of the Heart.

- 24K: unblocks the chest, lowers the Qi of the Lung and unblocks the Qi of the Liver, disperses heat, calms the Heart and Shen, treats cough, asthma.

- 18GB: Disperses Wind and Heat, calms pain, lowers the Qi of the Lung and subdues the Yang of the Liver, treats headaches and dizziness, nose problems, obsessive thoughts and excessive thinking.

- 10DM: Treats perverse Yang, eliminates toxic Fire (poison) from the skin (from redness to a boil), calms cough and wheezing as well as all respiratory disorders, treats acute stomach pain.

Good practice!

Author: Ivan BEL

Translator: Abigail Maneché

Notes:

- [i] Culturalist anthropology gives priority to symbolic explanation in the organization of a society

- [ii] Structuralist anthropology explains the diversity of social facts by combining of a limited number of logical possibilities related to the architecture of the human brain.

- [iii] “The superior doctor heals the kingdom, the middle doctor treats the human, the inferior doctor treats diseases” (上医治国, 中医治人, 下医治疗病), quoted in the article “Origins of Chinese Medicine: Daoist or Confucian?”, by Lokmane Benaicha, 2015.

- [iv] In the history of Chinese medicine there have been punches made of cut stone, but bone needles are more common.

- [v] In the Classic, the Yellow Emperor declares his intention as follows:

“I want to stop the administration of remedies that make my people even sicker

I want us to abandon the stone punches, to use only metal needles

That we prick the meridians in order to act on the knots (points) and energy

And to restore the right balance”

- [vi] Without entering this debate, I refer the reader to the book entitled “The origins of China” by Jacques Gossart which quotes many cases and works in this direction.

- [vii] The oldest text on Chinese medicine was found during the exceptional excavations of the Mawangdui site on bamboo strips. The tomb had been closed in 168 BC. This text speaks of meridians but not yet of acupuncture. The second text is the Shiji (Historical Memoirs) of the historian Sima Qian (145 to 86 BC) written between 109 and 90 BC. In this immense work, a treatment with needles is spoken of for the first time. The Classic of the Yellow Emperor thus comes in 3rd position, historically speaking, but it is actually a compilation of 20 much older medical treatises: Wu se, Ma bian, Shang jing, Xia Jing, etc., and among them the oldest of all, the Tài shǐ tiānyuán cè (太始天元册) hardly translatable as “The Book of the Great Beginning of the Original Heaven”. These treaties no longer exist today because most were burned in the autodafé (in 213 BC) of all ancient books and the burial of 460 scholars (alive) by the first emperor of China: Qin Shi Huangdi. These treaties were saved by Wáng Bīng 王冰 (710 to 805) who is the first commentator on the Classic of the Yellow Emperor. In particular, he restored seven missing chapters from the Classic of Yellow Emperor concerning the 5 movements (called Yun at the time before becoming Wuxing) and the 6 Qi (here the 6 climatic factors).

- [viii] In this regard, it should be noted that China is a notable exception in prehistoric history, as it passed without transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age without the long period of use of softer metals (such as copper) as was the case in the Middle East. The first bronze objects date from the Majiayao period (between 2700BC and 2300BC), which would correspond to the Chinese dating of the conference of the Yellow Emperor. But the Bronze Age really developed from 2100BC under the Xia Dynasty (夏朝; xià cháo from the 9th to the 7th century BC), which could just as well correspond with the words of the Yellow Emperor as well, the time that bronze was sufficiently popularized to make metal needles.

- [ix] Zhù yóu 祝由 is difficult to translate. It is composed of the verb “to wish, to bless” and “cause, reason, to follow, to let go”. This is shamanic medicine itself.

- [x] « The Spirit of points », Philippe Laurent, You Feng editions, 2010

- [xi] The Shuōwén Jiězì was written in the 2nd century by Xǔ Shèn (许慎; 58 – 147 AD). It is the first dictionary of Chinese characters to offer an etymological analysis of their composition and to classify them using what is now understood as keys. Its true title is “Origin (說) of the graphic form (文) and explanation (解) of the pronounced character (字)”.

- [xii] The effects cited are those found in the respective works by Philippe Laurent, Giovanni Maciocia, Philippe Sionneau and Alain Dubois.

- Anpuku Workshop with Ivan Bel in London – 7 & 8th, June 2025 - 22 June 2024

- Summer intensive course: back to the roots of Shiatsu – 7 to 13 July 2024, with Ivan Bel - 27 December 2023

- Interview with Wilfried Rappenecker: a european vision for Shiatsu - 15 November 2023

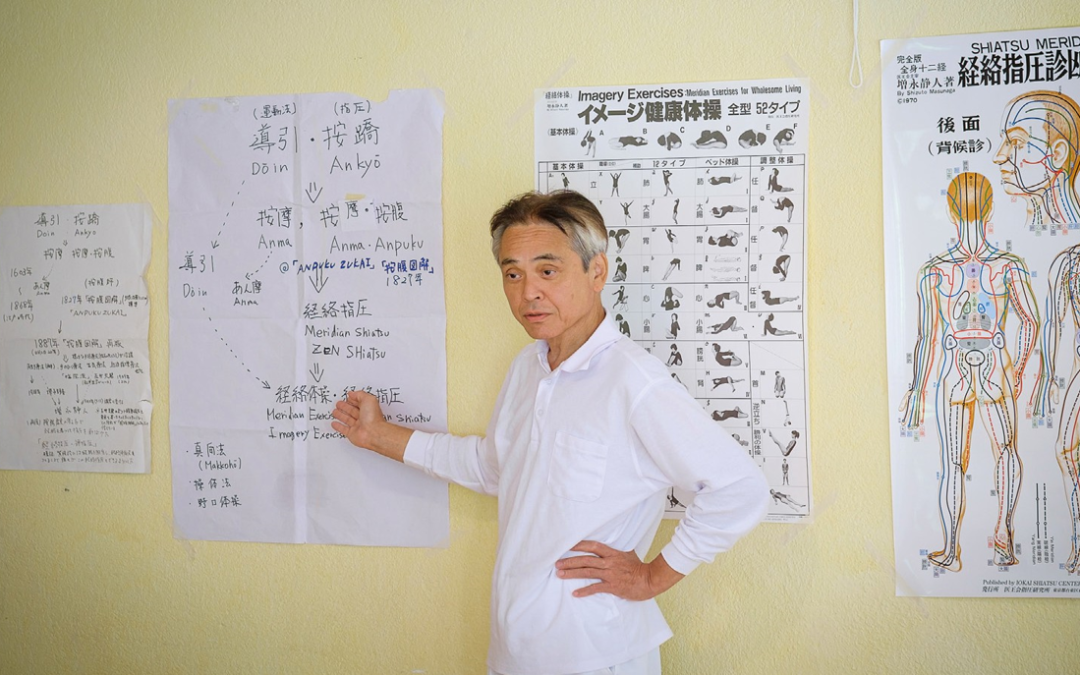

- Interview : Manabu Watanabe, founder of Shyuyou Shiatsu - 30 October 2023

- The points that chase away Dampness - 11 June 2023

- Interview Mihael Mamychshvili: from Georgia to Everything Shiatsu, a dedicated life - 22 April 2023