There is a lot to say about rhythms in Shiatsu. Shiatsu is a therapeutic art intrinsically linked to far-east medicine. This is, in turn, entirely related to the movements and rhythms of nature that ancient Chinese have observed for millennia. It is therefore logical that Shiatsu is the very representation of these rhythms and incorporates them into its techniques.

However, each style (I mean ryū 流, school’s stream) of Shiatsu seems to have crystallized around a precise rhythm in the pressure, to the point of making it their distinctive trademark. On the one hand this specialization is interesting because it allowed to study thoroughly what a particular rhythm can produce on the human body, in addition to the perpendicular pressure and the thrust (power) exerted. For example, Koho Shiatsu or Jigen Shiatsu, two styles of martial Shiatsu, have a very fast rhythm (approximately a second) and a strong enough pressure, while on the opposite Zen Shiatsu or Yin Shiatsu can spend a relatively long time on each point with lighter pressure. On the other hand these specializations prevent from appreciating all the pressure rhythms and from using them all. A bit like telling a mechanic to use only a 12mm wrench and not to touch any others in order to repair an engine, or a musician to play only one note. It seems disabling, right? That’s because it is.

The various rhythms

Between both extremes (very fast and really slow), there is a whole range of possibilities. They can be classified more or less as follows:

- Less than a second: precise strikes to perform a kuatsu (resuscitation technique) when a body weakens seriously or just after an injury.

- 1 second: very fast, this rhythm is used in Shiatsu of martial origins. It tones the body and the Yang. In this type of Shiatsu, it’s better to already be in good shape and sturdy enough, as are the martial arts practitioners.

- From 2 to 3 seconds: the pace is fast. It requires going back and forth on the same line several times to achieve an effect. This effect is both relaxing and invigorating, as it stimulates the Yang surface and energy while relaxing the inside through rebound. It is a very good pace to loosen up the mechanical and muscular problems and circulate the Ki.

- From 3 to 5 seconds: this rhythm presents a good balance between Yin and Yang. It allows to contact the Blood layer, to balance the body and the mind while deepening the receiver’s relaxation.

- From 5 to 12 seconds: this slow pace stimulates the Yin energy to re-energize a tired person. It contacts the deep layers and triggers the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. It usually requires only one pass per meridian.

- Beyond 12 seconds: here’s what is called connections (or “meditative thumb”), whose goal is to harmonize the energy between two tsubos, two meridians or between the receiver and the practitioner. This often happens between two points of contact (both thumbs or both palms).

If you want to be able to make a Shiatsu tuned to each case that comes into your practice, it’s interesting to play with all these pressure rhythms and not to limit yourself to a single way to proceed. This is why one must always be wary of dogmas and their “that’s the way it is”. In my classes I‘m used to saying, “If you have a fan that is folded over one notch and it’s hot, you can still shake it. You won’t get much air, the effect is almost zero! If you open it up completely, it will work much better.” When studies are done in clinics, as is the case when training full-time [1], teachings delve into all pressure rhythms. Some schools even go so far as to preserve the best in each style and to discard dogmas, in order to focus only on the therapeutic aspect. I quite agree with this vision of things which is very Anglo-Saxon and can be summarized as: “only the result counts”.

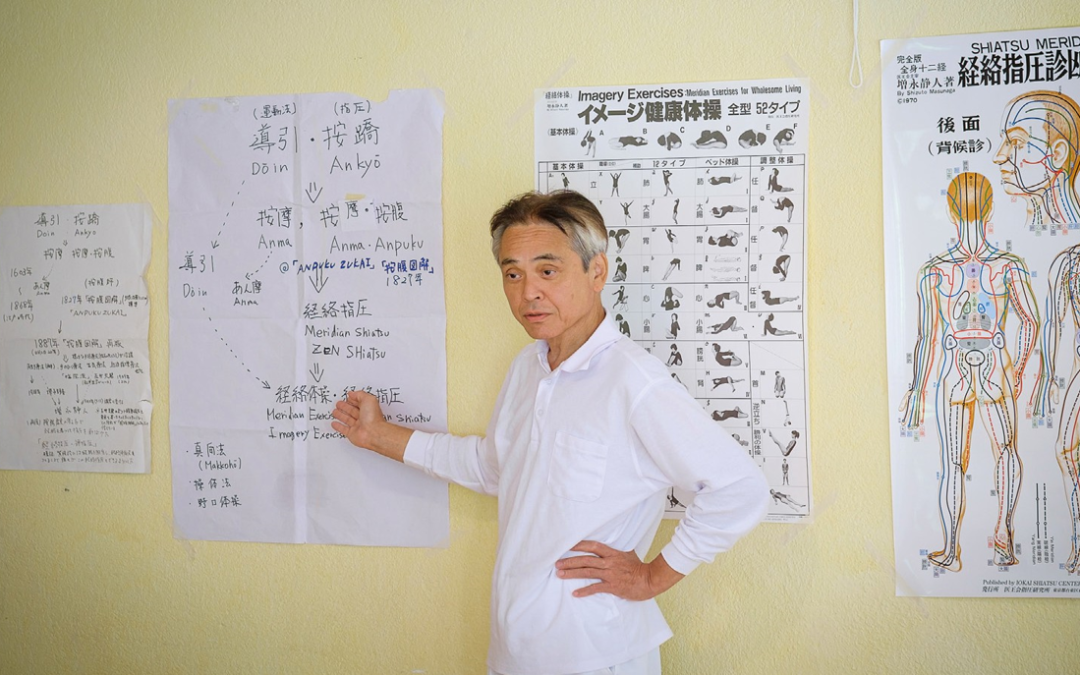

But this whole story about rhythms goes much further. One of the most competent teachers I have met in my Shiatsushi life is Bernard Bouheret [2]. Author of several books, very famous in France, he has been living Shiatsu for over 35 years. The greatest lesson you can receive from him is to watch him give a Sei Shiatsu. Unlike Shiatsu styles with a single rhythm, this one varies regularly within a treatment. He speaks of it as a musical symphony. There is the introduction, the main development, then, as for a music piece, ups and downs, quiet times like fast times, some sort of theme, then a smooth conclusion. The rhythm changes introduced are never abrupt. He doesn’t jump from one rythm to another, which would create a disharmony that would disturb the recipient. No, he does this in a continuous progression, as if you were driving in a landscape of rolling hills. This concept of setting to music and therefore automatically to rhythm, allows for great richness in the treatment and for constant rhythm and depth adaptation based on what the hands feel. In this way, the recipient has the feeling of being “explored” on all his facets. It’s a soothing and complete feeling at once, where nothing seems to have been forgotten. Kobayashi sensei, the senior instructor of Japan Shiatsu College in Tokyo, demonstrated in 2014 a comprehensive treatment in Brussels during an international seminar. Without a word and for almost one hour, his hands travelled the body like a pianist, moving from one rhythm to another, pausing when it was necessary, before continuing unabated. So, by applying this process, one does not get bored as a practitioner during the session and one can think of oneselves as real conductors, inventing one’s compositions, creating one’s scores, in short, following one’s intuition, one’s feelings.

And to further use the metaphor of a musician, imagine that a student has learned all the notes, and even several scales, but that in terms of rhyth, he gets frozen out: “in music, only the following rhythm is the right one, ta-ta-ta -ta … “, like a metronome. He then goes to the piano or any instrument and plays “ta-ta-ta-ta”, whatever the note. It would be dreadful, right?

If that’s true, then why continue practicing anything by following a single beat, whether it’s music or Shiatsu? Look honestly at your practice and what you were taught during your classes. Are you used to following a monotonous rhythm or are you able to play a real score? Do you know all the existing rhythms in Shiatsu? Have you tested their effects? Have you combined them with other principles of pressure? Once again, there is no single good way to go. Every school, every style of Shiatsu teaches us something, so you should not restrict yourself and confine yourself to a single way of doing things. The Ryoho Shiatsu that I teach systematically explores all variations in pressure rhythms, tempo, depth, strength and tests mechanical as well as energetic approaches, in order to open up the widest possible range of possibilities.

Silences

In music as in poetry, in painting as in discourse, what produces depth is not so much the rhythm as the silences we summon at the right time. The notion of silence is crucial. Knowing how to stop one’s fingers in a Shiatsu is like the icing on the cake. It’s a breathing, a pause between two sequences, which offers a moment of calm to the receiver as well as to the donor. In that very moment, nothing happens. The Shiatsushi listens to the body, deepens the connection, while jusha (the receiver) collects his strength or drifts off even further. The right time to take a break depends entirely on one’s ability to feel. If you come across pain, an area of tension, there is no point in insisting too much with the hope that it will dissolve. Sometimes you have to know how to wait, listen and accompany the receiver into the infinitely small, into the subtle. This is where the highlight of a whole treatment plays out, as if one were at the apex of a mountain before descending the other side.

The question that comes next is, how long does this break take? The balance is delicate and again you have to rely on your instinct and your listening. If you don’t do anything for an hour, the person in your hands will wonder why he or she came. If you leave too quickly, you risk missing something essential. Kawada Sensei used to say that he had once held pressure for 45 minutes until life returned to the point of interest (in this case, VC6, Kikai). Usually, it’s good to wait to feel even the faintest change in heat, blood circulation or muscle fibers. This is the signal that a process was triggered. Wait a little longer to make sure the process continues well and move on to the rest of your symphony.

Rhythm is not just an intellectual idea but rather a founding principle of the Shiatsu technique, which allows for the variation of effects and the creation of depth in your treatment. Better still, the practitioner can also occasionally rediscover the pleasure of applying one single rhythm, no longer because he can only do that, but because he has chosen to. Thus, after creating a space of freedom for the recipient thanks to pressure and some comfort thanks to stability, what it also creates is a space of creative freedom for him. With variations of rhythms and breaks in a Shiatsu score, all participants to a Shiatsu session find a reward and fully enter the concept of pleasure: the pleasure to be treated and the pleasure to give.

Ivan Bel

Translation by Gilles Datcharry

——-

- [1] As is the case in Canada or Japan with trainings spanning over two or three years of 2200h minimum.

- [2] Bernard Bouheret is the founder of Sei Shiatsu, the French Union of Professional Shiatsu Therapeutics(UFPST) and author of the essential “Vade Mecum – 108 treatments of Shiatsu”, published by Quintessence editions.

- Anpuku Workshop with Ivan Bel in London – 7 & 8th, June 2025 - 22 June 2024

- Summer intensive course: back to the roots of Shiatsu – 7 to 13 July 2024, with Ivan Bel - 27 December 2023

- Interview with Wilfried Rappenecker: a european vision for Shiatsu - 15 November 2023

- Interview : Manabu Watanabe, founder of Shyuyou Shiatsu - 30 October 2023

- The points that chase away Dampness - 11 June 2023

- Interview Mihael Mamychshvili: from Georgia to Everything Shiatsu, a dedicated life - 22 April 2023