Michel Odoul is no stranger to the world of Shiatsu, far from it. The success of his books, which have now been translated into many languages, has made him one of the leading thinkers in our world. But while these books are bestsellers, the man and his life are far less well known. We had done a radio programme together on the subject of Shiatsu, but had never met. And finally, in his office at the top of a Parisian building, surrounded by the books that have accompanied him for decades, he spoke freely about his career, his adventures, his training and his vision of Shiatsu. This is a great moment of sharing and a life lesson that I encourage you to read from cover to cover.

Ivan Bel: My first question may sound strange, but are you a true Parisian?

Michel Odoul: No, I’m an Auvergne native, from the Cantal to be precise, born in Aurillac. I spent the first 10 years of my life in the Auvergne volcanoes and my father was a forest ranger, so I grew up in the woods like a wild child. Changes in my father’s job meant that we gradually moved to another place, and I studied in Clermont-Ferrand at Sup de Co before looking for a job. When I started working, I moved to Paris. This led me to become a senior manager in a household appliance company.

Like all senior executives, I was leading a crazy life. We were in the 70s when a friend said to me: ‘Listen, if you need to de-stress, I practise a really good martial art called aikido, you should try it’. And that was my first encounter with the Orient. The teacher was Nakazono sensei[i], a leading aikido master who represented Japan in France (NDR: following Tadashi Abe Sensei and at the same time as Tamura Sensei and Noro Sensei). He was also a master of shiatsu and acupuncture, and a university lecturer in traditional Japanese medicine, whose references he knew by heart. One day, when he was giving an initiation to Shiatsu, my wife and I decided to give it a try. At the time, my wife was suffering from knee pain. The doctors had told her there was nothing wrong with it. She was happy to be told that, but she was still limping and in pain. When Nakazono sensei saw her coming, he asked her what was wrong, got her to lie down and pressed a point on her ankle, even though her knee was hurting. She screamed in pain and afterwards her knee never hurt again. We came across a vision of the world and of the body that made our neurons jump a little because it was able to respond to a problem where our Western vision could not. Being curious by nature, I wanted to go further afield, and the journey never stopped, to the point where I had to leave everything behind to devote myself entirely to this study, which in the late 70s was not an easy choice for anyone to make.

How old were you when you made this choice?

So wait (he thinks for a moment)… I was 25 when I made that choice.

That’s a very early stage in life!

Yes, it must have resonated with something deeper. So, was it this childhood in nature, seeing living things in direct contact and not through a TV screen, I don’t know. But one thing’s for sure: by observing, listening to and respecting living things and nature, you stop philosophising, because you’re in touch with something concrete. And this reality is rich in lessons. This is what I found through Aikido, because behind the martial art there is an absolutely incredible philosophy of life, as well as an understanding of what the systems of our universe are, how to manage the flows of life and the futile nature of ‘fighting against’. And as I’d studied economics and business management, where you learn how to manage flows and use them, there was a kind of connection in my mind. So, in the early years, I used the flow management I’d learnt in Aikido and Shiatsu as a method of managing conflicts in the workplace. [ii].

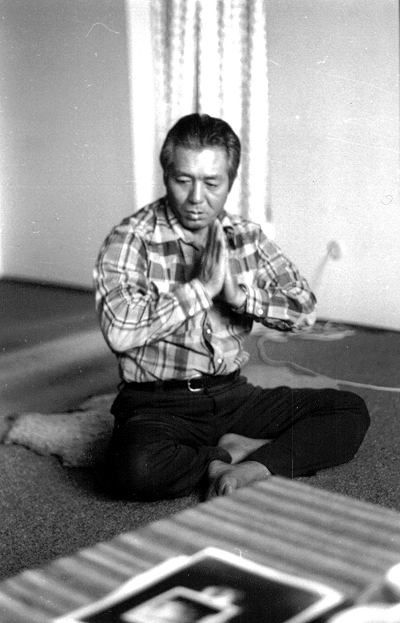

What kind of man was Nakazono sensei?

He was a samurai, as you can see from his works. If you read them literally today, you think ‘what kind of madman is this? He had the uncompromising rectitude of the samurai and was therefore someone who was difficult to follow. In fact, several of his assistants were unable to complete their apprenticeship. His last assistant in France, Philippe Ronce, was unable to follow him when he left for the United States, for example. [iii]. I was only able to follow him for one year, but what a legacy he left me!

Then I followed one of his Aikido and Shiatsu assistants, Pierre Molinari[iv], who was also a fan of the Way, in other words someone who was totally committed to what he was doing, like our master. Let me give you an example: for Nakazono sensei, arriving five minutes before a shiatsu session was out of the question. His day had to be prepared, because the first rectitude imposes itself on the practitioner. So you had to arrive early, prepare your body, clean the room, meditate, etc. For him, the practitioner’s posture was not a privilege, but a duty, an obligation to behave correctly, with the whole code of Bushido underpinning it. Nakazono’s second peculiarity was that after a certain level he didn’t explain anything. If you wanted more, you had to go and get it, work, observe and commit yourself further. For a basic Western mind, this was particularly annoying (laughs), so only those who stuck with it could succeed.

What type of Shiatsu did he teach?

He had learnt the styles of Namikoshi and Masunaga in particular. But he was a specialist in Kampo medicine and acupuncture, so he made his own synthesis. The first of his specificities was that he always said ‘if you touch the global, you will always touch the local. But if you only touch the local, you’ll never touch the global. Before doing anything to correct a specific imbalance, you have to touch the whole body to prepare the ground’. He prepared the ground by starting to reopen all the Assent points on the back[v]. In this way, he worked on the 12 meridians, because his vision of Shiatsu, beyond the osteo-articular technique, was to act on the meridians. The second specificity of his Shiatsu was the ability to work precisely on a choice of pressure points (tsubos) to correct an imbalance. In this way, he worked as much on the quantitative side of energy (toning – dispersion) as on the qualitative, notably by using the ancient points. So after preparatory work to open the Shu points on the back, which opened the floodgates and provided a first level of balancing, he chose a specific treatment according to what he had found through the history, observation of the eyes, the tongue, the posture, the pulse, and so on. Then come the techniques, which are of two kinds.

- Osteoarticular: reopening joints, relaxing muscles…

- And energy work: with digital pressure or moxas.

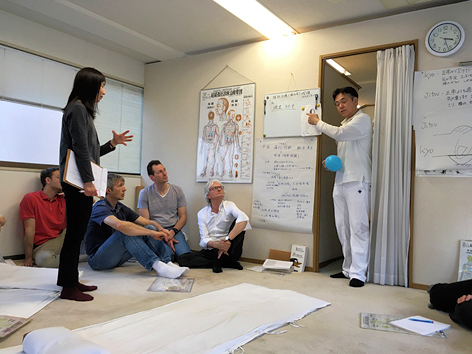

It’s a complete body of work, a bit atypical in the world of Shiatsu, and it’s of great interest to the Japanese, like the Masunaga son. The same was true when I invited the teaching team from the Namikoshi school to visit me, or when I met them in Tokyo. You could say that the idea of a complete Shiatsu tickles them.

How did you go about your apprenticeship?

With Pierre Molinari, for 23 years in a row, because he worked like Nakazono sensei. You had to stick with it. I went from student to assistant, then I taught Aikido and Shiatsu in his dojo at Porte d’Ivry. Of course, Shiatsu is an osteo-articular, muscular and energetic technique, but we had to learn to go beyond the technique by putting into it what we were studying elsewhere, our parallel research. Nakazono sensei used to say to us: ‘What you put into Shiatsu depends only on how much space you decide to put into it’. That’s when I became interested in the psycho-emotional field, because I realised that this was one of the areas where this practice was lacking. At least in what was expressed. It’s well known in theory that such and such a meridian corresponds to such and such an emotion, etc., but the Orientals don’t talk much about this, because they express it in a different way. At that point I said to myself, well, we’re lucky in the West because we know a lot about this area. I became interested in the work of all the greats of modern psychology, Freud, Jung, Adler, Berger, Frankel, etc., and I began to read across the board and to cross-reference emotions with psychosomatic reactions. I compiled this over many years and thousands of hours of sessions, which led me to write the book ‘Dis-moi où tu mal…’ (Tell me where it hurts…). (Editor’s note: see the list of books at the end of this article). I compared all this with what the Japanese and Chinese thought, particularly at the Guang An Men Hospital in Beijing.

I read the book you’re quoting very early in my life, in my twenties, and I’ve always asked myself this question: how did you come to discover the mechanisms of bodily ailments? Was it a transmission or a personal search?

It was both. It was also a transmission, but it wasn’t organised, it wasn’t structured and it wasn’t expressed in words that we could understand in our psychological language. Moreover, when Nakazono arrived at the dojo, he never knew what he was going to teach. He would smell people and start a topic. But that gave me my first challenge as a teacher, which was to organise all this knowledge, to synthesise it for Western students in order to come up with a clear, comprehensible teaching method, reduced to its essence. The essence of teaching is not only the art of teaching clearly, but above all knowing how to give others what they are capable of receiving.

After compiling the data, I did some statistics, because I like philosophy and ideas, but I’m also very concrete. So I observed the repetition of phenomena on this or that meridian, over and over again, until I was able to draw a conclusion of cause and effect. It was my job to make this synthesis and then to reverse the proposition and be able to say that if a person suffers from such and such a problem, perhaps he’s suffering from such and such a cause.

Let’s go back a bit. You were studying in the 70s and at what point did you become a practitioner?

In ‘82. In other words, there was a whole period before that when I was doing this alongside my work, for food reasons. I had to feed the family. But at a certain point it became impossible, between the intensive training courses and the courses I had to take, I was faced with a choice. So I looked for a way to make the transition to professional Shiatsu. At the time, there was a blockbuster film called ‘Star Wars’. My nephew used to say to me ‘it’s a shame there aren’t any laser swords, they’d be so cool’. Then one morning as I was walking my wife to work, it was still dark at the end of October, I saw the police in traffic with their white glow sticks. That’s when things clicked in my head. I immediately started making drawings, plans, a statement of accounts for the savings account, contacted the injection mould manufacturers and in 8 days I had produced the first toy lightsaber for children before George Lucas. I filled the boot of the car, went round the toy shops in Paris and at Christmas it was an unimaginable success. For 3 years I sold these sabres, and by 82 I’d saved enough to get started and in 86 I gave my first lessons.

It’s a funny story: here’s a side of you that we don’t know. Back in 82, when you first set up shop, I imagine that the word ‘Shiatsu’ meant nothing to anyone.

It was a dirty word. Simply a big word. The only way to do it was to convince people, to use word of mouth, in short it took a long time, but that’s why I had anticipated and created a fund by selling all the rights to the light sabre. It took three years before I had enough customers to make a living from it. In short, it was a gamble on the future.

Did you open directly here, at the Institut Français de Shiatsu?

No, I started teaching in 86 in Pierre Molinari’s room at Porte d’Ivry. Here it was 10 years later, in 96.

What prompted you to open this institute?

I felt I wanted to do more and have a place of my own, because to create an identity you need a unity of place. It was also a question of economics, because opening a centre in Paris is not the same as opening one in a provincial town where a square metre is 10 times cheaper. I looked around for a long time, visiting a whole host of offices to rent, but I really liked the Gobelins area. Then, as I was driving along rue Monge, I came across a rental sign right here. I parked the car, took the phone number, the man from the agency could come straight away, I fell in love and signed the same evening. There was just one problem! I didn’t have enough money to pay the rent. I had to work very hard again, and it was another leap of faith to embark on this new adventure. But the desire was there and, as we often say, it was stronger than me. It had to be in this place with this view (editor’s note: the institute overlooks the church of Saint-Médard in the Vème district) and this light. That’s how I came to create the institute that I’m so happy with today.

After all, it was one of the very first training centres in Paris, wasn’t it?

Not one of the first, but in that dimension and structure, yes. It has to be said, and this is not a value judgement, that a lot of training centres had a cottage industry feel to them. I wanted both my approach and the place to be indisputable, respectable and to make people want to come. I trained in basements, on tatami mats that smelt of sweat, with neon lighting, but I didn’t want to impose that on my students. On the other hand, I’ve kept the Japanese rules: you start on time and you finish on time. If someone’s late, they don’t get in. It took me a while to impose this discipline and many people were unhappy about it, but it didn’t matter. That’s how I wanted to teach.

Finally, how long have you been practising Shiatsu?

Oh no, you can’t say that… (laughs). Over 40 years in any case.

That’s what’s so great about it: you can see that the years go by, but the passion is still there, still learning, still discovering. It’s bottomless! I’d like to come to your vision of Shiatsu. Do you see it as bodywork, an energy technique or something else?

That’s what it’s all about! In Shiatsu I find a similarity with Aikido. It’s a process. In my institute, I believe that I teach not only know-how, but also interpersonal skills. This means that being a Shiatsu practitioner is not just about giving advice. It’s about being upright, having an open view of the world, having the ability to listen to what life and living things have to offer, it’s about being part of a philosophy of life in which we find the codes of Bushido and Shinto. To sum up, benevolence fraternises with exacting standards, which may appear to be antinomic, but in reality are profoundly inseparable. The right kindness means being a solid branch to which the other person can cling, and that presupposes the work of rectitude on a daily basis. For example, it’s good to brush your teeth, but it’s also important to clean your roots. It’s like polishing a blade. It has to be done gently, and it needs time.

Tell me about this concept of time.

The concept of time often leads to a paradox. Students have a diploma in their hand and have studied for 4 or 5 years, so they immediately see themselves as very strong, capable of working and sometimes even teaching. But this study also implies a notion of stages, and it’s important to know where you are in your progression, a journey that is immense. As a result, you have to take patients at their own level and not try to go too fast. Where the problems arise in this progression linked to time is when notions of omnipotence emerge, and the fascination we have with wanting to achieve a result. It’s at times like these that we push ourselves too hard and make excessive choices, ultimately wasting energy and making mistakes. We don’t dictate the pace of our progress. It’s part of a process of living, of demanding more of ourselves on a daily basis, in terms of the amount of work we do, of course, but also in terms of our capacity for endurance. As a teacher, it’s also a process that’s reflected in the demands we make of our students and in our ability to give them what they can absorb. You won’t be a good practitioner or teacher until everything has matured from within. To achieve this, you don’t need to dress up as a Japanese or burn incense all over the place – this isn’t Kathmandu. What we do need is to be in the here and now, in this world, in this life, with all the presence we can develop for ourselves and for others.

It takes time to make this journey. You spoke of stages, but there are also desert crossings.

There are even moments of regression, it’s a normal process. To explain desert crossings, I illustrate this to my students by explaining what a sick person is. A sick person is an insect in the moulting phase. It’s cramped in its shell and wants to tear it apart. That’s why it hurts. So anaesthetising this pain at this point can have dramatic consequences, as it can lead the evolving individual to regress. Then, while waiting for his new skin to harden, he is fragile. And that’s the state the patient is in, and for him it’s a journey through the desert until he reaches his new state of equilibrium. But it’s important to remember that the practitioner is also going through things. For them, there are two phases of danger: when the wind is blowing in their direction, they feel buoyed up, become euphoric and run the risk of bursting into flames; when the wind is blowing against them, they start to doubt. In both cases, it’s very dangerous! Euphoria, or the intoxication of success, is when the practitioner makes mistakes. Doubt is when great practitioners stop everything, and that’s a great pity. In my opinion, to avoid these pitfalls, you have to remain anchored in your day-to-day practice, in the high standards I was talking about earlier. That way, you can get past your personal desert and reach a new level.

I come back to my earlier question: is Shiatsu a purely osteo-articular or energetic technique, or something else?

The East as a whole, whether Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean or Japanese, fundamentally accepts the idea of the vibratory nature of our universe. As a result, tensions, imbalances and states of harmony are all managed through energy. The question that then arises is: what interfaces do I use? I can use nutrition, for example, as an interface to regulate vibratory energy, in the form of Chinese energetic dietetics. I can use acupuncture. I can use moxibustion and finally body techniques. Shiatsu is part of this, in other words, it uses finger pressure on precise points or zones – even in Namikoshi’s vision – to inform, communicate and rebalance an energetic state. It doesn’t matter whether we use fascia, scalar waves[vi], cosmic frequencies or other explanatory vectors. It’s just a question of language and organisation of thought, and having worked with practitioners of all styles, they all do energetics like Monsieur Jourdain does prose, sometimes without knowing it, but sometimes with better results than those who only do intentional work.

So, to answer your question, Shiatsu is a bodily technique, which allows us to have an osteo-articular action. It is also, of course, an energetic technique. And finally, Shiatsu is a psychosomatic technique, because during the history-taking phase, when the practitioner asks the patient a few questions, through this simple open door, he suggests that something other than a symptom may appear.

What is this other thing that appears?

Perhaps the root of the problem for which it comes. Let’s use an analogy. Take a guy who wasn’t told he had to disengage the clutch to drive his car. Crack, crack, crack. Of course, he ends up breaking his gearbox. He takes his car to the garage and the mechanic finds the fault and changes the gearbox. The guy is happy, he drives off with his car without any further information, and crack, crack, he does it again. As long as no one has explained to him that you have to disengage the clutch to change gear, he will continue his pathogenic and accident-inducing behaviour. Consequently, in the field of curative medicine, there is the Yin dimension, which is the physical dimension, but we mustn’t forget the Yang dimension, which is not just energy, but also the question of meaning. And that’s why I went looking in that direction, because it’s fundamental. Of course, people have said ‘Odoul, he’s not doing Shiatsu, he’s doing psychology’, but that doesn’t matter, because as time goes by, the question of meaning becomes more and more topical. Thanks to this research, I’m taking part in a D.U. in medicine in Strasbourg to talk about mind-body links and so on. Nobody can deny the importance of patients’ quest for meaning in their illnesses.

In my Shiatsu practice, I’ve noticed a change over the last ten years. People no longer just want relief, they want to understand why they are ill.

Yes, and that’s why we can try to run away from this question all we want, but sooner or later we’ll be caught up in it. It’s only logical! When a child falls, the mother gives him a kiss on the spot where he hurt himself. The pain is gone and he goes back to playing. What is the treatment? Psycho-emotional. Full stop! We go straight to the root of the problem. But to do nothing but psycho-emotional treatment is to forget the bodily dimension, and in Shiatsu that’s a mistake. It’s like telling the driver to change the gearbox without teaching him how to disengage, it’s a mistake.

Which means that in Shiatsu there is also a patient education dimension?

Not educational, but informational. In my opinion, Shiatsu has no educational pretensions. Or maybe we need to discuss what we mean by this word. On the other hand, the patient must not leave as he arrived. They have to reappropriate their part of the problem. It’s a subtle game, because it shouldn’t be the practitioner who says what the problem is. On the other hand, as he knows, he leads the patient to understand his problem and eventually to express it. This generates a phenomenon of insight in the patient, who says to himself ‘by golly, this is the cause of my problem’. And that’s when the person accepts and is finally able to move on to the next part of their story. This is perhaps where its ‘educational’ dimension lies.

Since the practitioner is not silent, what is the role of therapeutic speech in Shiatsu? First of all, should we speak as a practitioner?

Of course you can! The way I teach it, the interview lasts at least 20 minutes, and that’s important. There’s no chit-chat and no ‘café du commerce’ psychology, but guided discussion. There’s a way of conducting the history-taking which, in the very particular way of Chinese medicine, ensures that the patient finds meaning in his or her problem. We have a duty to inform, but not to convince. And, of course, we have a duty to give advice on nutrition, lifestyle, Qigong or Taichi practices and, if necessary, to recommend other practitioners or doctors. These are all fundamental elements of the practitioner’s responsibility.

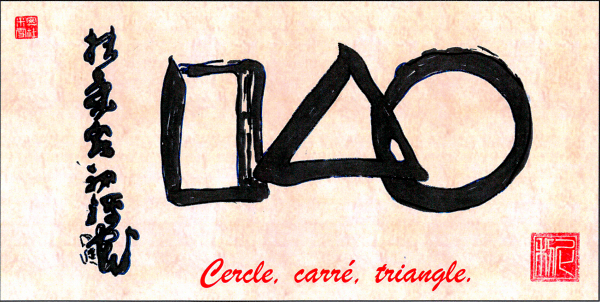

In 2015 you published three books in one go, the three volumes entitled ‘Fundamental Shiatsu’. When I read Volume 3, I thought it would be good to bring the reader back to Japanese philosophy, and not just Chinese Taoist philosophy, as well as the important concepts of this culture. There’s one that really speaks to me, and I’m going to give it to you in the form of a drawing: the triangle, the round and the square. Why is this important?

So, how shall we put this? It’s Earth-Man-Sky… the ability to remake Unity. This reconstitutes the three fundamentals – symbolic, structural and energetic – of our universe and our world. What makes a Romanesque abbey feel so good? Because this architecture is based on the circle and the square – Earth and Heaven. As for the triangle, it is the representation of man inserted in the middle of the other two. These are energy symbols that help us to understand how the whole is organised and to accept that ‘Heaven directs and Earth carries out’. It’s the acceptance of a non-religious transcendence that is both macrocosmic – the way in which the external Sky orders and the Earth reacts and organises itself – and microcosmic – our own Earth, i.e. in our body and also in our internal Sky, our psyche -.

After that, these symbols can be found just about everywhere, and they cut across most of the world’s cultures – Amerindian, African, Western and Asian – because they are part of the archetypes. In the martial arts, for example, they are the three fundamental positions for executing any technique.

And how can these three symbols be used in Shiatsu?

Above all through posture. The triangle in Shiatsu is above all the practitioner’s seated position (Editor’s note: seiza) with the three support points of the two knees and the feet together.

Is it also the ability to realign a person in their body and in their relationship to the world?

That’s it! And the central triangle then becomes the practitioner capable of realigning the person between their body (square) and their sky (round). There are many possible explanations, as this is one of the great symbolic representations of the world and the Universe, along with the Tao, the Yin/Yang, the spiral and so on.

In the fundamental concepts of Shiatsu, you also put a lot of emphasis on the notion of ‘Misogi’[vii]. Do you teach this to your students?

Yes, of course. As in Aikido, this notion of inner cleansing is essential. In fact, we have a two-day training module to teach practitioners how to cleanse themselves. We use the 50 postures handed down by Nakazono sensei, which correspond to the 50 sounds of the Kototama. In the Kototama there are 5 mother sounds just as there are 5 energy principles[viii] and we make links between the two. Ueshiba sensei[ix] used to do Misogi as well as Kototama, and he had a sound for each gesture he made in those moments. This is what we find in the last form of his art, which he called Takemusu Aïki. But as much as he clearly explained what had to be done for Misogi (exercises, prayers, etc.), he was cautious about the Kototama, which he refused to teach. So much so that Nakazono had to go and see a master called Ogasawara Koji Sensei (author of ‘The Soul of Words’ or Kototama, in 1964) to learn it, because apart from living a monastic life, this art cannot be passed on like a simple technique. That’s why I don’t teach it either; I give a few keys to understanding that can be inserted into Shiatsu, that’s all. Misogi, on the other hand, can be worked on seriously.

When you say the word ‘seriously’, we sense that you are demanding at all times.

A fundamental idea that is not specific to Shiatsu alone, but to the whole field in which we practise, is to understand that practising an alternative medicine does not allow us to be vague or nebulous, and to base ourselves on our feelings alone. Quite the opposite is true. If you claim to be working in subtle fields, you have to be more demanding than if you were just using a mechanical technique. Alternative approaches will do a world of good the day they realise that they need to clean up their act. We have to be careful what we say and what we do, because the tendency is to go a bit too lightly and too quickly. Everything needs to be justified and explained.

This means that you really have to act to the best of your knowledge and belief. This means that you have to be as demanding in your know-how as in your interpersonal skills, which leads you to become an upright person and not to become, as we say in Shinto, a ‘deceitful’ person, i.e. someone who takes the wrong path because they try to avoid things, to let themselves go, not to study everything thoroughly. The difficulty for today’s practitioners is to understand that even if you’ve reached a certain level, you must never forget to do your scales, nor forget all the intermediate layers between the beginning and the end of an action, otherwise you’ll never get good results. In other words, it’s the journey that counts.

To conclude this interview, I’d like to end with a comment I often hear, to the effect that Shiatsu studies are long and require too much commitment to follow, and are therefore discouraging. What do you think about this?

You have to ask yourself one question: would these people send their mother to be treated by someone who was trained in 15 days or 6 months? (laughs). That’s a very basic question, but I think it sets the record straight. It’s valid in all fields, but particularly in the formatting period that is teaching, because it’s a formatting, to become a practitioner worthy of the name.

Let’s take the image of the Japanese blade polisher. He receives forged steel in the shape of a sword, but that is not enough. He has to give it a shine, a reflection, and work for a long time to achieve this. The polishers – who are all the students – have to work on their blade or their soul, which can be written both ways. Of course, you can do family or comfort Shiatsu, and work with that, no problem, it doesn’t take much time. But when you want to claim to be able to welcome someone who is suffering, then you’re not playing games any more. You have a responsibility, and the action you take as a practitioner can have catastrophic consequences if you’ve been trained quickly, or life-saving consequences if you’ve taken the time to study and work on yourself. Someone once said, I’m sorry I can’t remember who, but here’s the quote: ‘Time does not respect what is done without it’.

Thank you so much for sharing this moment with us.

Thank you for coming.

(C) photo credits: courtesy of Michel Odoul.

Notes :

[i] Mutsuro Nakazono (1918-1994) was a master of the martial arts (especially Judo and Aikido) and Japanese medical practices (Shiatsu, Acupuncture and a specialist in Kototama, the art of sound) who lived in Japan, the USA and France. He was one of Christian Tissier shihan’s first teachers. Lire la biographie de Nakazono by Léo Tamaki.

[ii] This method has become quite common today and many business coaching companies offer this tool, known as AïkiCom or Verbal Aïkido.

[iii] In 1972, Nakazono moved to Santa Fe (New Mexico) to escape the hassles of the medical association because of his good results. There, however, he opened a number of clinics, was quickly recognised for his talent as an acupuncturist and was behind one of the first American laws governing the practice.

[iv] Pierre Molinari is the author, with Georges Brunon, of ‘Le geste créateur et l’Aïkido’ (published by Editions du Rocher, 1980). Above all, he is one of only four advanced adepts in Kototama trained by Nakazono (along with Jean-Claude Tavernier, Philippe Ronce and Fabien Maman).

[v] The Assent points are the Shu points (in Chinese) or Yu points (in Japanese), the so-called Transport points.

[vi] Scalar waves have a spiral shape, with different properties to electromagnetic waves. To find out more, read the article d’Alternative Santé n°63, December 2014.

[vii]Misogi (禊) is a Japanese concept that comes from Shinto and can be translated as ‘purification’. It is associated with a set of techniques for cleansing the body and mind of kegare (impurities), generally at the summer and winter solstices.

[viii] See Wuxing and the five energy movements.

[ix] Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969) is the founder of Aikido. To find out more, lire la biographie de Ueshiba on Fudoshinkan.eu by Ivan Bel.

Bibliography by Michel Odoul

About Shiatsu :

- L’harmonie des énergies, éditions Albin Michel, 2002

- Shiatsu et réflexologie pour les nuls, First Editions, 2009

- Shiatsu fondamental, Tome 1, Albin Michel 2014

- Shiatsu fondamental, Tome 2, Albin Michel 2014

- Shiatsu fondamental, Tome 3, Albin Michel 2014

- Le Shiatsu, PUF, 2017

- Shiatsu Fondamental, Dunod 2019

About the mind-body connection:

- Dis-moi où tu as mal, je te dirais pourquoi, Albin Michel, 2002

- Dis-moi pourquoi cela m’arrive Maintenant, Albin Michel, 2016

- Dis-moi quand tu as mal, je te dirais pourquoi, Albin Michel, 2013

- Dis-moi où tu as mal, le lexique, Albin Michel, 2003

- Aux sources de la maladie, Albin Michel

- La phyto-énergétique, avec Elske Miles, Albin Michel, 2004

- Cheveu parle-moi de toi, avec Rémi Portrait, Albin Michel, 2002

- Un corps pour me soigner, une âme pour me guérir, Albin Michel 2011

- Les médecines alternatives en 40 pages, Poche, 2016

- L’animal en nous, Albin Michel, 2011

- Face à la mort, ouvrage collectif sous la direction de Jacques Delga, MA Editions, 2018

Author

- A Milestone: The 2025 ESF Symposium in Brussels - 24 March 2025

- Austria – 19-21 Sept. 25: Shiatsu Summit in Vienna – chronic fatigue, burnout & depression - 19 December 2024

- Terésa Hadland interview: Shiatsu at core - 25 November 2024

- Book review: “Another self” by Cindy Engel - 30 September 2024

- Austria – 24-26 Oct. 25: Master Class in Vienna – Shiatsu and martial arts - 20 August 2024

- France – Lembrun Summer Intensive Course – July 6 to 12, 2025: Digestive System Disorders, Advanced Organ Anatomy, and Nutrition - 4 August 2024