The human pelvis is far more than a skeletal structure — it is a crossroads of anatomy, evolution, sexuality, and energetic medicine. The uniquely rounded and prominent glutes of Homo sapiens are evolutionary adaptations for upright posture and have acquired strong symbolic and sexual meanings across cultures. Beyond its sociocultural implications, the pelvis functions as a vital container in both Western and Eastern medical traditions. In Chinese medicine, it houses the Ming Men, the “fire of life,” linked to the extraordinary meridians that shape the entire body. The text also examines how posture and movement are governed by the Qiao Mai meridians, which harmonize Yin and Yang, sleep and wake cycles, muscular and visceral activity. This finely tuned system, when well-aligned, allows the Jing to flow and nourish the brain — the Sea of Marrow — promoting health throughout the body.

Some food for thought

The pelvis between bipedalism and sexuality

TThe part of our body commonly referred to as the “pelvis” has been highly regarded by all human-developed cultures, precisely because of its importance in many of the most significant aspects of both cultural and natural life.

When we talk about this anatomical region, unless one has an in-depth knowledge of anatomy, the first visual association that often comes to mind is the back of the pelvis (the so-called “B-side”), where we can observe two rounded shapes that are considered unusual when compared to the rest of the animal kingdom.

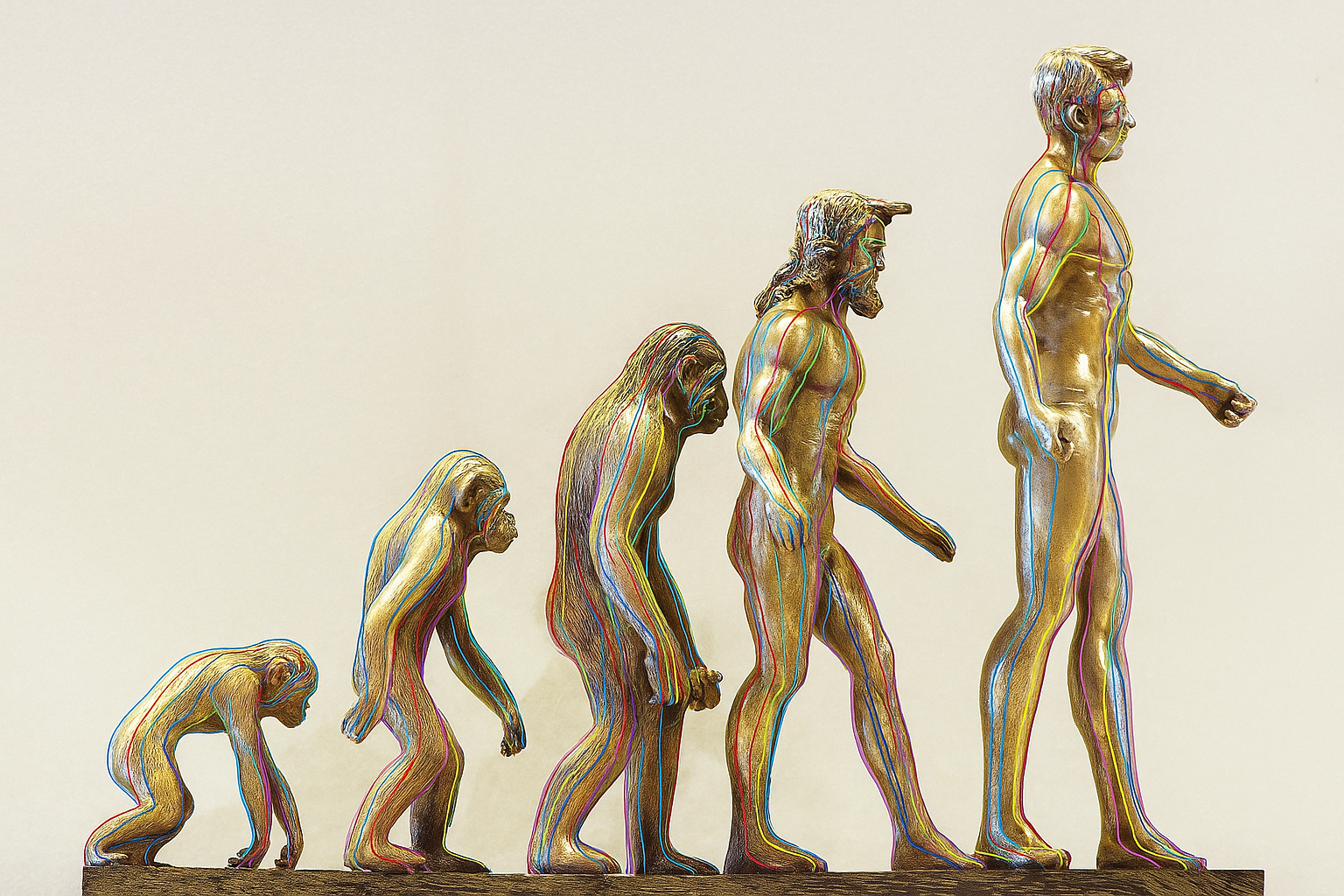

Indeed, although all other animals possess gluteal muscles just like the Homo genus, in our species these muscles have developed a different shape and size, making us the clear winners when it comes to having the largest glutes relative to body size.

These peculiarities are linked to specific bone features that changed during our evolution. Together with the gluteal muscles, these adaptations allow us to stand upright.

The bipedal position that we have reached at this point in our (still ongoing) evolution has caused significant changes in certain physical characteristics. As Desmond Morris points out in his essay The Naked Ape, the shift from a quadrupedal to a bipedal stance resulted in female genitals becoming more concealed. Most likely, the roundness and size of the buttocks (which, in some cultures, is particularly appreciated when voluminous) acted in our species as an alternative sexual signal, as they are clearly visible in the upright posture and closely related to the genitals.

The accumulation and distribution of fat in this area is strongly influenced by the hormonal cycle, helping us understand the high erotic significance of this anatomical region.

Another secondary sexual characteristic that likely developed in relation to the changes mentioned above is the female breast. In other animals, the nipples swell only when offspring are born and the mammary gland develops. In human females, however, the mammary gland develops at sexual maturity.

It is very likely that the roundness of the breast visually echoes, from the front, the roundness of the buttocks. This trait has proven to be advantageous due to the change in posture and the more frontal approach with different partners.

The B-side of our evolution

As far as we can understand from evolutionary mechanisms, it is likely that the sequence of changes occurred as follows:

- A progressive change (probably favored by random mutations) in the position of the pelvis—and consequently of the gluteal muscles—allowed certain individuals to gain an advantage over others who lacked these characteristics.

- Greater advantages translated into a higher probability of survival and of passing these traits on to offspring.

- A consequent modification in sexual signals, which became considered attractive, arose in response to the new upright posture.

TThe inclination of the pelvis is indicative of the strength of Kidney Yang and is closely related to sexuality. In general, a more pronounced lumbar lordosis tends to belong to a woman with stronger and more expressive Kidney Yang, associated with greater sexual vitality. Conversely, a person who holds the pelvis as if they had their tail between their legs will often express a less intense sexuality and typically a less active Kidney Yang.

The round shape of the buttocks, and the fact that such a shape is uniquely human, did not go unnoticed by our ancestors, who identified this characteristic as exclusively human. As a result, they attributed its absence to the Devil, who was often considered a being without buttocks. The devil, aware of this lack and envious of humanity, could not bear the sight of bare buttocks. From this belief arises the superstitious custom of mooning (showing one’s bare backside) to ward off evil and keep the devil away.

From Ming Men to Primitive Node: the fire of Life

Of course, the pelvis is not made up solely of the buttocks—however fascinating they may be—but rather is a true basin or container of fluids, composed of the iliac bones, pubis, and sacrum. This structure is designed to hold precious elements, and in the world of Eastern medicine, it contains the Ming Men Fire, the source of life itself.

The 3 Cavities and Extraordinary Meridians

To draw a comparison, we might equate the Ming Men with an embryonic structure that occupies a similar location: the Hensen’s node or Primitive Node. This structure appears in the Primitive Streak, which will later form the notochord, the precursor to the central nervous system—or Du Mai, upon which the Ming Men point is still identified, at the level of L2–L3.

The primitive node guides embryonic cells to their appropriate destinations, just as the Ming Men orders the development of the entire bodily structure based on a Ming or “Mandate.” From this structure emerge the first-generation Extraordinary Vessels:

- Chong Mai

- Dai Mai

- Ren Mai

- Du Mai

These four first-generation extraordinary vessels form the trunk, with its organs and all associated structures. Within this structure, three main cavities are later identified, which in classical Chinese medicine are known as the “Bone Cavities” and are associated with the Curious Organ “Bone” (Gu). The Six Curious Organs (Bone, Uterus, Gallbladder, Vessels, Brain, Marrow) are those that ensure the flow and movement of Jing and are the most subject to transformation during evolutionary processes. In particular, the Bone and the Brain are the ones that change the most. in classical Chinese medicine are called bone cavities and are associated with the curious bowel bone – GU. The six curious viscera (bone, uterus, gall vesicle, vessels, brain, medulla) are those that ensure the progression and movement of the Jing and are more prone to change during evolutionary processes. In particular, the bone and the brain are the ones that change the most.

The Three Bony Cavities in Oriental Medicine and the Curious Organ “Bone”- GU骨

In Classical Chinese Medicine, the three main cavities of the human body—pelvis, thorax, and skull—are not merely anatomical containers, but true energetic centers deeply connected to the Three Treasures: Jing, Qi, and Shen.

Pelvis – in relationship with Lower Dan Tian

It is the seat of Jing, the vital essence. Involved in reproductive processes and energetic grounding. The point Ming Men (DU4) is fundamental for the nourishment and warmth that supports this cavity.

Thorax – in relationship with Middle Dan Tian

Center of Qi, the circulating vital energy. It is related to respiration and digestion. The anterior Shu points, particularly those of the Kidney meridian (KI22–KI27), regulate the energetic balance of the thoracic cavity.

Skull – in relationship with Upper Dan Tian

Seat of Shen, the mind or spirit. It is connected to consciousness, intuition, and mental clarity. The Window of Heaven points harmonize cranial energy and promote communication between body and mind.

Interconnection and the Role of the Du Mai

The three cavities are connected along the spinal column through the Du Mai meridian, which represents a vertical energetic axis. Points GV4 (Ming Men) and GV14 are true energetic hubs that maintain the integrity of the structural system by influencing the cervical (GV14) and lumbar (GV4) lordosis, the dynamic regions of the spine that govern the spatial relationship among the three cavities.

The Curious Organ: Bone – Gu 骨

In this framework, bone is considered one of the Curious Organs because it stores Jing and protects the cavities where fundamental energies reside. Bones are not inert elements, but living, resonant structures that reflect the deepest qualities of the individual.

Postural alignment

TThe three cavities align thanks to the vertebral column, and this alignment allows for optimal circulation of the Jing to nourish the “Sea of Marrow”—that is, the brain. On this note, a scientific study is worth mentioning that highlighted how the skeletal system has a sub-periosteal fluid transmission mechanism that helps regulate joint pressure. (Pitkin, M. R. (2024). Modeling of the Effect of Subperiosteal Hydrostatic Pressure Conductivity between Joints on Decreasing Contact Loads on Cartilage and of the Effect of Myofascial Relief in Treating Trigger Points: The Floating Skeleton Theory.)

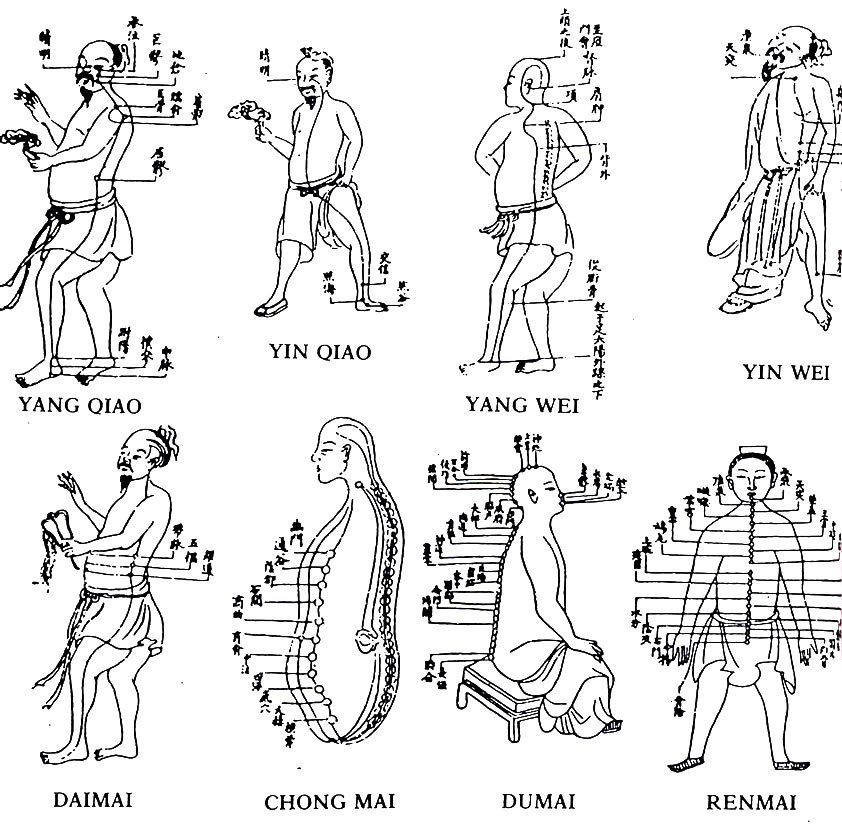

Once the trunk has been formed, we witness the emergence of the limbs from the cavity outlined by the four first-generation vessels. The formation of the limbs corresponds to the development of the second-generation extraordinary vessels. These are:

- Yin and Yang Qiao Mai

- Yin and Yang Wei Mai

These meridians are in part very similar and in part very different from the first-generation extraordinary vessels. Jeffrey Yuen describes them as structures that are halfway between the functions of the first-generation extraordinary meridians and the primary meridians. In particular, the Qiao Mai are described as the Luo of all Yin and all Yang.

Given their deep relationship with the limbs, we can consider the second generation—and in particular the Qiao Mai, which connect strongly to the heel and link it to the eye (BL1)—as fundamental structures in regulating the postural alignment of the three bone cavities.

Heels, eyes and Posture: a delicate balance

When we speak of alignment, it’s important to stress that we’re not referring to a “correct” or “ideal” alignment, but rather to a flexibility of alignment that prevents stagnation. Alignment is subject to a range of individual factors, both structural (anatomical differences) and functional (e.g., right- or left-handedness), which make a perfectly symmetrical and aligned body impossible.

Our goal is to ensure that alignment remains as elastic and adaptable as possible. This, in my view, is the modern concept of “Correct Posture.”

There are several articles that provide evidence of a functional relationship between ankle position and the tension or relaxation of the pelvic muscles.

There are also many references highlighting how the relationship between feet/ankles and eyes is crucial for optimizing upright posture coordination.

Returning to the Curious Organ Bone and the changes it has undergone through evolution, we can identify some important transformations that enabled our postural shift:

The big toe shifted its position and acquired a propulsive function.

- A change in the orientation of the iliac bones and the femoral neck altered the leverage available to the gluteal muscles, allowing for a more effective action in upright posture.

- The presence of one or two additional lumbar vertebrae (some people have six lumbar vertebrae instead of five) compared to apes contributed to a more efficient lumbar lordosis for weight distribution in upright posture.

- The heel became wider and better suited to support weight.

The use of fire and our skull shape

To these changes in the lower body, we must add equally important changes in the upper body:

- The use of fire to cook food allowed for a reduction in jaw size while enabling cranial expansion.

- The brain could grow due to this increased cranial capacity and, most importantly, thanks to a greater availability of nutrients from cooked food.

The expanding brain and the progressive ability to use the hands are associated with a more active Shen.

Control over the sensory orifices and hands—used to manipulate the world—is enabled by the control of the neck, governed by GV14, and by eye-hand coordination, which we can understand by considering the functional union between the Ting points of the Yang meridians of the upper limb and the ST8–GB13 area, which brings together these muscular meridians.

The pelvis and Children’s developement

As a child grows, they first learn to manage cervical lordosis and orient their sensory orifices. Then they try to reach for them, learning to coordinate eyes and hands in order to grasp objects and bring them into their world through the mouth.

However, when the desired object is too far away, greater willpower is needed to move toward it. GV4 provides this strength directly from the Kidneys, helping to activate the muscular meridians of the lower limbs, which provide the propulsive force to bring the child closer to their goal—first by creeping, then crawling, and finally by standing up to free the hands and carry the toy.

This progression allows the gradual formation and control of lumbar lordosis (GV4).

A functional connection then develops to manage the upright posture between the muscular meridians of the lower limbs and the head. The Ting points of the Yang meridians coordinate with the SI18 area, forming a foot-eye connection.

Other connections that support upright posture coordination include:

- and the Ting points of the Yin meridians of the upper limbs with thoracic points GB22–23.

- the Ting points of the Yin leg meridians with the anterior pelvic points (CV2–7),

Yin and Yang Qiao as conductors of orchestra

To coordinate all of this, two extraordinary vessels are used, also known as the “heel vessels,” which connect the heel to BL1, traveling through the Yang channels to coordinate all Yang meridians and through the Yin channels to coordinate all Yin meridians and Yin functions—such as internal organ peristalsis—which must be considered to manage posture.

These structures are Yin and Yang Qiao, which thus become responsible for coordinating all Yang and all Yin.

- Yang Qiao coordinates the dynamic aspects of the musculoskeletal system, as well as the regulation of wakefulness and cortisol rhythms in response to light. It is important for coordinating the circulation of Wei Qi during the waking phase.

- Yin Qiao, on the other hand, coordinates static posture, the relationship of peristalsis with the rest of the body, nighttime rhythms, and the melatonin cycle—facilitating falling asleep (KI6) and the return of Wei Qi to the torso to support sleep (ST12).

The combined treatment of these meridians, along with special attention to points more related to the bone cavities (BL61, GB29, SI10, to name the most important), can improve the relationship between the internal cavities and the external muscular system. This fosters a flexible and adaptable alignment, allowing Jing to flow freely to nourish the Sea of Marrow (the brain), and thereby support overall health and well-being.

Conclusion – One Pelvis, Many Stories

The pelvis, always at the center of our bodily structure, posture, and even sexual expression, proves to be a key region for understanding human evolution, vitality, and health. It’s not just a biomechanical base—it’s a crossroad of hormones, posture, sexuality, ancestral energy, and both neurological and symbolic connections.

We’ve traveled from the embryonic node to the extraordinary meridians, from upright posture to the links between heels, eyes, and desire. We’ve seen how the aesthetics of the glutes—often reduced to mere appearance—actually hold an entire evolutionary and symbolic narrative that bridges East and West, science and myth.

But what happens when this structure loses its flexibility, when our “container” stiffens or goes out of alignment?

What is the pelvis telling us today about our health, our relationships, and our way of inhabiting the world?

Perhaps it’s from the center that we must begin again, to rebuild balance.

Author

- The Pelvis: Anatomical, Cultural and Energetic Evolution - 8 September 2025

Translator

- USA: 3rd Annual Shiatsu Summit – April 17/19, 2026 - 26 January 2026

- 2nd Balkans Shiatsu Summit – in Zagreb (Croatia), April 11 & 12, 2026 - 11 January 2026

- Belgium: depression and burn-out with Shiatsu – June 19-21, 2026 in Ostend - 7 January 2026

- An intensive week to explore Emotions and Psychological Disorders – 5-11 July 2026 - 6 January 2026

- Switzerland: Shiatsu Principles and Concepts course – October 16-18, 2026 in Saillon - 10 December 2025

- Italy: Shiatsu Workshop – Energy Principles and Vacuum Concept (Xuli) in Shiatsu – 31 Jan. and 1 Feb. 2026 in Padova - 4 November 2025