In the world of Shiatsu, everyone performs stretches while naming the meridians being stretched. These exercises are called Makkō-hō and are often attributed to Shizuto Masunaga. In this in-depth article, Stéphane Cuypers follows the principle of “don’t believe what you see or hear, but dig and investigate” to verify the facts. Two things quickly emerge from his research: the Makkō-hō exercises we know have nothing to do with the original version, and it was not Masunaga who developed them.

This article is highly recommended for all Shiatsu teachers and practitioners. One could even say it’s good for both your health and your knowledge!

In our Eastern treasure chest, we actually have quite a few techniques involving stretching, breathing, posture… which we sometimes practice and teach to our clients. These are commonly referred to, in no particular order, as Do In, Qi Gong, self-shiatsu, or other names. One of the most frequently mentioned terms is undoubtedly Makkō-hō, generally understood to mean “the meridian stretches invented by Mr. Masunaga.”

But it’s just like the history of Shiatsu until quite recently: everyone repeats what they’ve heard (myself included — as you’ll see if you make it to the end of the latest article), and almost no one checks the sources. And so, just a few hours of focused research allowed me to uncover some previously unpublished facts, which now simply need to be organized and shared.

So, here it is:

- What we call Makkō-hō is not the original Makkō-hō, as it still exists in Japan today;

- Shizuto Masunaga does not speak of Makkō-hō — he offers “visualized exercises”;

- There is a common foundation to all these practices, but also some fundamental differences.

What Makkō-hō means

This is a rule we can no longer afford to ignore: when faced with a Japanese concept, we must look at the etymology by examining the kanji. Carefully. Google Translate is very approximate and often doesn’t provide the correct readings of the kanji (there are usually two ways to pronounce them, to keep it simple). As for book translators, they often tend to fantasize and tie meanings to Western concepts they know — concepts that have nothing to do with the original Japanese idea. So, the best approach is to look at the kanji and line up their meanings side by side, without interpreting them through a Western mental framework. There are excellent online dictionaries for this purpose.

In the case of Makkō-hō, there are three kanji:

- Ma 真, also pronounced Shin, carries the ideas of truth, reality, authenticity, and seriousness. For example, it also appears in the word “photography.”

- Kō 向 conveys the notion of direction, inclination, tendency, going toward, or pointing toward.

- Hō 法 refers to law, act, principle, method, or technique… For instance, the book by Tempeki Tamai is titled Shiatsu-hō — it’s the same Hō, meaning “Method of Shiatsu.”

- Small detail: It is pronounced with long vowels Kō and Hō, which should be written with a flat macron (“ō”) and pronounced as long sounds. The short Ko and Ho, of course, mean entirely different things.

Makkō-hō, then, means “method of Makkō” — a method that leads us toward, or brings us back to, authenticity, seriousness, and truth. Tomoko Morikawa Morganelli, a practitioner of traditional Japanese Makkō-hō, translates the term as “to look straight forward.” But what does Makkō have to do with stretching?

The answer likely lies in the true Makkō-hō, as it is still practiced in Japan today.

Origins of Japanese Makkō-hō

It was an English acupuncturist, John Dixon, who put me on the trail of today’s Japanese Makkō-hō. He speaks of four exercises, whereas we usually refer to six. Tracing this back to Japan reveals some interesting discoveries.

It was Mr. Wataru Nagai who, in 1948, brought the exercises of Makkō-hō into prominence. The son of a Buddhist monk, he was pursuing a business career when he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Declared incurable and left physically impaired, he began reciting Buddhist sutras. In his childhood temple — Shōman-ji near Fukui (only identifiable by the kanji: 福井県の勝鬘寺) — there is a seated practice that involves “bending forward from the waist” before the Buddha.

Feeling that he should bring more gratitude into his life, Mr. Nagai began practicing this form. He soon discovered he was blocked due to his stroke, but, in true Japanese spirit (gambatte kudasai, as they say), he persevered — and after three years of practice, he fully recovered his physical abilities.

In 1948, during the postwar period and with the aim of encouraging the Japanese people, Wataru Nagai began teaching and spreading these health exercises under the name Makkō-hō [1]. His son, Haraku Nagai, even published a book in 1972 titled Makkō-hō: 5 Minutes’ Physical Fitness [2], and traveled to the West during the 1970s to promote the practice. Historically, this aligns with the development of Shiatsu and fits the pattern of exporting Japanese techniques to the West. It seems, however, that the method never took deep root outside Japan, except through two practitioners in the United States.

Cultural and Religious Background

When we talk about a practice “in a Buddhist temple,” what exactly should we relate it to? There are, in fact, many differences among the various schools of Japanese Buddhism. It was an FAQ from the official Makkō-hō website that led me down this path. A frequently asked question in Japan, it seems, is whether Makkō-hō is linked to religion. The official foundation denies any such link: Makkō-hō is recognized by the Japanese government as a public-interest foundation and a purely health-focused method. However, the site does acknowledge that the founder, given the Buddhist roots of his practice, initially called it “nembutsu gymnastics.”

The nembutsu [3] is a core practice of Pure Land Buddhism, in which believers simply repeat a phrase in order to be reborn in the Pure Land after death: “Namu Amida Butsu,” which means homage to Amida Buddha (the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life). Since Japanese Buddhism is known for its many branches and schools (the word “sect,” often used, is actually a poor translation), it made sense to check whether the Shōman-ji Temple near Fukui — identified as Wataru Nagai’s home temple — was indeed part of the Pure Land tradition.

It is — but specifically of the Shinshū school [4] (more precisely, a major branch of it called Ōtani-ha), founded in the 13th century by a monk named Shinran. So, Makkō-hō has its spiritual roots in Jōdō Shinshū, the Pure Land School — specifically from the Shōman-ji Temple near Fukui.

Why is this important? Because it helps us understand the mindset behind the exercises, and the spirit that necessarily inspired the founder.

So what characterizes Buddhists of the Shinshū lineage?

Why is this relevant, if not to understand the spirit at the heart of these exercises — the spirit that, inevitably, lived within the founder?

What characterizes Buddhists of the Shinshū tradition?

Shinshū believers recite the nembutsu (a contraction of Namu Amida Butsu), as they believe they will be reborn after death in the Pure Land Paradise, thereby becoming a Buddha themselves. It is therefore an act of faith — without specific requests, and without the need to earn merit through long studies or prolonged meditation. The name of Amida contains the idea of saving all beings. This brings peace of mind. Grace saves — not personal effort. (But note: there is no god involved, and this is a key difference from Zen, which rejects the notion of reliance on any external force.)

Even the monks themselves live in the world and say that one should live “according to the honest customs of one’s time” (as stated by Emile Steinilber-Oberlin in Japanese Buddhism). Clergy marry, eat meat and fish… there are no extreme or inaccessible practices for ordinary people immersed in modern life.

This practice is therefore aimed at ordinary people (without any disparagement), those living “in time and in the world,” who neither have the time nor the means to sit long hours on a cushion or to lose themselves in metaphysical subtleties.

Amida’s unconditional love for human beings, and the gratitude it awakens in the heart, are powerful and sufficient foundations for morality. Everyone judges for themselves.

These, then, are some of the cultural and spiritual roots in which Makkō-hō is grounded, since its first promoter was deeply immersed in them. The translation “to look straight forward” makes much more sense when viewed through the lens of Pure Land Buddhism. We also understand that these exercises are simple, accessible to all, require no special effort, take little time, and allow gratitude and joy to be expressed.

Coincidence? While reading the Japanese Makkō-hō website in English, I noticed an interesting semantic shift: Pure Land Buddhism has given rise to a Pure Health Method.

Mind-Body Unity

We also understand that the body expresses an inner state through its posture (and in turn influences it), and that therefore the action targets both body and mind (in the broad sense), since it originally involved bowing as an expression of gratitude. The aim is to strengthen both body and spirit, to face life directly and live positively. The official website speaks of sharing the joy of good health — bringing us back to the joy of the Heart, which manifests fully when the organs function in harmony.

The daily practice of these exercises thus aims at several effects:

- Anti-aging, a very Japanese concern. This is made possible through flexibility and a cheerful disposition. I’ve seen it myself in Japan — many elderly Japanese people bounding up temple staircases like rabbits, chatting happily. Aging is often the result of atrophy, due to poor or insufficient use of the body.

- The work focuses on the tanden, hips, sacrum, spine, and on the symmetrical rebalancing of the pelvis.

- Breathing is essential.

- The effects are seen in joint condition, flexibility, posture, blood circulation, breathing, and the nervous system.

- Whatever one’s current condition, progress will come gently — leading eventually to the natural flexibility of a child.

- The aspect of gratitude for life and joy in the practice is fundamental. It is a joyful practice.

Only Four Exercises

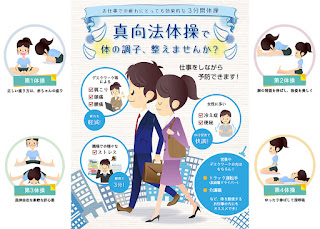

A screenshot from the official Makkō-hō website in Japan presents the essentials in a slightly naïve contemporary Japanese style. Even without reading Japanese, the illustrations make the message clear. There are four exercises, each lasting about three minutes, that help ordinary people — when they’re stressed at work, feeling down, or lacking vital warmth. Behind this, there is a whole structure: levels of Makkō-hō, group classes offered at affordable prices.

- The first exercise works on opening the pelvis and is said to relate to an ancestral way of sitting.

- The second consists of bowing — but in a seated position.

- The third opens the inner thighs.

- The fourth involves back bending and wariza (or suwahiro), a low sitting posture between the feet.

While practicing all this, one must not forget harakokyu — breathing (ko = exhale, kyu = inhale) into the belly.

To look straight forward: the movements are exclusively front-to-back. It is a life attitude — moving forward without looking to the sides.

This feels familiar to us, as in Mr. Masunaga’s stretching series:

- The first matches exactly with Heart/Small Intestine,

- The second with Bladder/Kidneys,

- The fourth with Stomach/Spleen.

As for the third, it appears identically in Mr. Kawada’s series of Extraordinary Vessel stretches, where it corresponds to the Yang Linking Vessel (Yang Wei Mai) [5].

However, the attribution of these stretches to specific meridians came later and does not reflect the original spirit of the practice.

Therefore, we cannot rightfully call our usual stretches “Makkō-hō.”

Japanese Specificities

The core elements of Makkō-hō are deeply rooted in Japanese culture:

- Bowing is not limited to the various forms of rei in martial arts — it is a matter of everyday etiquette. By bowing, one expresses respect… with many subtle gradations.

- Sitting is not just something done in a Zen temple for shikantaza (“just sitting”) [6], but a fundamental bodily posture in daily life, reflecting the vertical alignment between Heaven and Earth.

- The value of Makkō-hō lies in the fact that it was discovered through personal experience and sensation, and not borrowed from a pre-existing catalogue of exercises. This empirical approach is at the heart of what we do.

And to truly absorb the spirit of the origins… all that’s left is to watch and practice.

Here’s a video of Makkō-hō as practiced in Japan. A beautiful lesson in atmosphere — especially for us, who often practice stiffly and seriously, in our fine outfits and silent temples…

This happens during festivals — collective, simple, joyful, and for all ages.

That’s the Japan of the people — the real one.

Or this practitioner who suggests sequences to prepare the movements and… look closely at the end, to see how it strengthens the hara!

With that clarified, let’s see what can be said about Mr Masunaga’s exercises.

[To be continued]

Notes

- [1] Editor’s note: This exercise was adopted as a preparatory practice by the founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, who met Wataru Nagai in 1959 and resonated with his teachings and practical skills. Makko-ho is known as a preparatory exercise for Aikido practice.

- [2] “Makkō-hō – Five Minutes’ Physical Fitness,” by Haruka Nagai, Japan Publications (USA), January 1st, 1972.

- [3] Yūzū Nembutsu-shū (融通念仏宗) is a Japanese Amidist school. For more information, see the corresponding Wikipedia article.

- [4] The Pure Land Buddhist sect (Jōdo, 浄土 in Japanese) refers to the Western Realm of Bliss. It is a major school within Mahāyāna Buddhism.

- [5] Editor’s note: Another notable influence in these exercises is that of Hatha Yoga, with postures such as Supta Virasana, Dandasana, Baddha Konasana, and Paschimottanasana.

- [6] Regarding shikantaza, see the article by Buddhist monk and Shiatsu master Ryotan Tokuda.

Author:

- The True Japanese Makkō-hō - 14 April 2025

Translator:

- USA: 3rd Annual Shiatsu Summit – April 17/19, 2026 - 26 January 2026

- 2nd Balkans Shiatsu Summit – in Zagreb (Croatia), April 11 & 12, 2026 - 11 January 2026

- Belgium: depression and burn-out with Shiatsu – June 19-21, 2026 in Ostend - 7 January 2026

- An intensive week to explore Emotions and Psychological Disorders – 5-11 July 2026 - 6 January 2026

- Switzerland: Shiatsu Principles and Concepts course – October 16-18, 2026 in Saillon - 10 December 2025

- Italy: Shiatsu Workshop – Energy Principles and Vacuum Concept (Xuli) in Shiatsu – 31 Jan. and 1 Feb. 2026 in Padova - 4 November 2025